Smear campaign

| Part of the Politics series |

| Political campaigning |

|---|

|

|

|

A smear campaign, also referred to as a smear tactic or simply a smear, is an effort to damage or call into question someone's reputation, by propounding negative propaganda.[1] It makes use of discrediting tactics. It can be applied to individuals or groups. Common targets are public officials, politicians, heads of state, political candidates, activists, celebrities (especially those who are involved in politics), and ex-spouses. The term also applies in other contexts, such as the workplace.[2] The term smear campaign became popular around the year 1936.[3]

Definition

[edit]A smear campaign is an intentional, premeditated effort to undermine an individual's or group's reputation, credibility, and character.[4] Like negative campaigning, most often smear campaigns target government officials, politicians, political candidates, and other public figures.[5] However, public relations campaigns might also employ smear tactics in the course of managing an individual or institutional brand to target competitors and potential threats.[6] Discrediting tactics are used to discourage people from believing in the figure or supporting their cause, such as the use of damaging quotations.

Smear tactics differ from normal discourse or debate in that they do not bear upon the issues or arguments in question. A smear is a simple attempt to malign a group or an individual with the aim of undermining their credibility.

Smears often consist of ad hominem attacks in the form of unverifiable rumors and distortions, half-truths, or even outright lies; smear campaigns are often propagated by gossip magazines. Even when the facts behind a smear campaign are demonstrated to lack proper foundation, the tactic is often effective because the target's reputation is tarnished before the truth is known.

Smear campaigns can also be used as a campaign tactic associated with tabloid journalism, which is a type of journalism that presents little well-researched news and instead uses eye-catching headlines, scandal-mongering and sensationalism. For example, during Gary Hart's 1988 presidential campaign (see below), the New York Post reported on its front page big, black block letters: "GARY: I'M NO WOMANIZER."[7][8]

Smears are also effective in diverting attention away from the matter in question and onto a specific individual or group. The target of the smear typically must focus on correcting the false information rather than on the original issue.

Deflection has been described as a wrap-up smear: "You make up something. Then you have the press write about it. And then you say, everybody is writing about this charge".[9]

In court cases

[edit]In the U.S. judicial system, discrediting tactics (called witness impeachment) are the approved method for attacking the credibility of any witness in court, including a plaintiff or defendant. In cases with significant mass media attention or high-stakes outcomes, those tactics often take place in public as well.

Logically, an argument is held in discredit if the underlying premise is found, "So severely in error that there is cause to remove the argument from the proceedings because of its prejudicial context and application...". Mistrial proceedings in civil and criminal courts do not always require that an argument brought by defense or prosecution be discredited, however appellate courts must consider the context and may discredit testimony as perjurious or prejudicial, even if the statement is technically true.

Targets

[edit]Smear tactics are commonly used to undermine effective arguments or critiques.

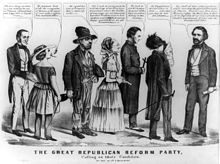

John C. Frémont – 1856 US presidential election candidate

[edit]

During the 1856 presidential election, John C. Frémont was the target of a smear campaign alleging that he was a Catholic. The campaign was designed to undermine support for Fremont from those who were suspicious of Catholics.[citation needed]

General Motors against Ralph Nader

[edit]Ralph Nader was the victim of a smear campaign during the 1960s, when he was campaigning for car safety. In order to smear Nader and deflect public attention from his campaign, General Motors engaged private investigators to search for damaging or embarrassing incidents from his past. In early March 1966, several media outlets, including The New Republic and The New York Times, reported that GM had tried to discredit Nader, hiring private detectives to tap his phones and investigate his past and hiring prostitutes to trap him in compromising situations.[10][11] Nader sued the company for invasion of privacy and settled the case for $284,000. Nader's lawsuit against GM was ultimately decided by the New York Court of Appeals, whose opinion in the case expanded tort law to cover "overzealous surveillance."[12] Nader used the proceeds from the lawsuit to start the pro-consumer Center for Study of Responsive Law.

Gary Hart – 1988 US presidential candidate

[edit]Gary Hart was the target of a smear campaign during the 1988 US presidential campaign. The New York Post once reported on its front page big, black block letters: "GARY: I'M NO WOMANIZER."[7][8]

China against Apple Inc.

[edit]In 2011, China launched a smear campaign against Apple, including TV and radio advertisements and articles in state-run papers. The campaign failed to turn the Chinese public against the company and its products.[13]

Chris Bryant

[edit]Chris Bryant, a British parliamentarian, accused Russia in 2012 of orchestrating a smear campaign against him because of his criticism of Vladimir Putin.[14] In 2017 he alleged that other British officials are vulnerable to Russian smear campaigns.[15][16]

Blake Lively

[edit]In 2024, The New York Times reported on a smear campaign conducted against actress Blake Lively after she accused Justin Baldoni of misconduct. The smear campaign, which was led by Melissa Nathan and Jed Wallace, pushed negative stories about Lively and used social media to boost those stories. Nathan previously worked for clients such as Johnny Depp, Drake and Travis Scott.[17]

Overstock critics

[edit]In January 2007, it was revealed that an anonymous website that attacked critics of Overstock.com, including media figures and private citizens on message boards, was operated by an official of Overstock.com.[18][19]

UAE smear campaigns

[edit]In 2023, The New Yorker reported that Mohamed bin Zayed was paying millions of euros to a Swiss firm, Alp Services for orchestrating a smear campaign to defame the Emirati targets, including Qatar and the Muslim Brotherhood. Under the ‘dark PR’, Alp posted false and defamatory Wikipedia entries against them. The Emirates also paid the Swiss firm to publish propaganda articles against the targets. Multiple meetings took place between the Alp Services head Mario Brero and an Emirati official, Matar Humaid al-Neyadi. However, Alp’s bills were sent directly to MbZ. The defamation campaign also targeted an American, Hazim Nada, and his firm, Lord Energy, because his father Youssef Nada had joined the Muslim Brotherhood as a teenager.[20]

See also

[edit]- Attack ad

- Bullying

- Borking

- Cancel culture

- Character assassination

- Deception

- Destabilisation

- Disinformation and Misinformation

- Doxing

- Idealization and devaluation

- Kompromat

- Minimisation (psychology), also known as "discounting"

- Mudslinging

- Noisy investigation

- Manipulation (psychology)

- Red herring

- Red-baiting

- Red-tagging in the Philippines

- Setting up to fail

- Shame campaign

- Social undermining

- Swift boating

- Tone policing

- Tu quoque

- Whispering campaign

- Zersetzung

References

[edit]- ^ "SMEAR CAMPAIGN | definition in the Cambridge English Dictionary". dictionary.cambridge.org. Retrieved 2020-10-20.

- ^ Jay C. Thomas, Michel Hersen (2002) Handbook of Mental Health in the Workplace

- ^ "Google Ngram Viewer". books.google.com.

- ^ Roddy, B. L. and G. M. Garramone . ( 1988 ). Appeals and strategies of negative political advertising, Journal of Broadcasting and Electronic Media, 32, 415 – 427 .

- ^ Vaccari, Cristian; Morini, Marco (28 Feb 2018). "The Power of Smears in Two American Presidential Campaigns". Journal of Political Marketing. 13 (1–2): 19–45. doi:10.1080/15377857.2014.866021. ISSN 1537-7857.

- ^ Dezenhall, Eric (2003). Nail 'em: confronting high-profile attacks on celebrities & businesses. Amherst, N.Y: Prometheus Books. ISBN 978-1-59102-047-9.

- ^ a b William Safire. (May 3, 1987). "On Language; Vamping Till Ready". The New York Times.

- ^ a b Matt Bai. All The Truth Is Out: The Week That Politics Went Tabloid. Knopf (September 30, 2014) ISBN 978-0307273383

- ^ Pelosi, Nancy (2017-03-05). State of the Union (Television production). CNN.

- ^ Longhine, Laura (December 2005). "Ralph Nader's museum of tort law will include relics from famous lawsuits—if it ever gets built". Legal Affairs.

- ^ "President Dwight D. Eisenhower and the Federal Role in Highway Safety: Epilogue — The Changing Federal Role". Federal Highway Administration. 2005-05-07.

- ^ Nader v. General Motors Corp., 307 N.Y.S.2d 647 (N.Y. 1970)

- ^ Greenfield, Rebecca (27 March 2013). "China's Apple Smear Campaign Has Totally Backfired". theatlanticwire.com. Archived from the original on 9 November 2013. Retrieved 8 October 2013.

- ^ "I'm a victim of Russian smear campaign, says MP photographed in underwear". Telegraph.co.uk. 23 November 2012. Archived from the original on 2022-01-12. Retrieved 27 January 2017.

- ^ Knowles, Michael (15 January 2017). "Russian spies turn attention to British politicians in 'project smear', warns Labour MP". Express.co.uk.

- ^ Townsend, Mark; Smith, David (14 January 2017). "Senior British politicians 'targeted by Kremlin' for smear campaigns". The Guardian. Retrieved 27 January 2017.

- ^ "'We Can Bury Anyone': Inside a Hollywood Smear Machine". New York Times. 2024.

- ^ Antilla, Susan (February 21, 2007). "Overstock Blames With Creepy Strategy". Bloomberg News Service.

- ^ Mitchell, Dan (January 20, 2007). "Flames Flare Over Naked Shorts," The New York Times.

- ^ Kirkpatrick, David D. (27 March 2023). "The Dirty Secrets of a Smear Campaign". The New Yorker. Vol. 99, no. 7. Retrieved 27 March 2023.