1992 Los Angeles riots

| 1992 Los Angeles riots | |||

|---|---|---|---|

Aftermath of the riots | |||

| Date | April 29 – May 4, 1992 (6 days); 32 years ago | ||

| Location | |||

| Caused by |

| ||

| Methods |

| ||

| Resulted in | Riots suppressed

| ||

| Parties | |||

| |||

| Casualties | |||

| Death(s) | 63[2] | ||

| Injuries | 2,383 | ||

| Arrested | 12,111[3][4] | ||

| Damage | $1 billion | ||

The 1992 Los Angeles riots (also called the South Central riots, Rodney King riots, or the 1992 Los Angeles uprising)[5][6] were a series of riots and civil disturbances that occurred in Los Angeles County, California, United States, during April and May 1992. Unrest began in South Central Los Angeles on April 29, after a jury acquitted four officers of the Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD) charged with using excessive force in the arrest and beating of Rodney King. The incident had been videotaped by George Holliday, who was a bystander to the incident, and was heavily broadcast in various news and media outlets.

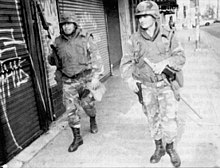

The rioting took place in several areas in the Los Angeles metropolitan area as thousands of people rioted over six days following the verdict's announcement. Widespread looting, assault, and arson occurred during the riots, which local police forces had difficulty controlling. The situation in the Los Angeles area was resolved after the California National Guard, United States military, and several federal law enforcement agencies deployed more than 10,000 of their armed responders to assist in ending the violence and unrest.[7]

When the riots had ended, 63 people had been killed,[8] 2,383 had been injured, more than 12,000 had been arrested, and estimates of property damage were over $1 billion, making it the most destructive period of local unrest in US history. Koreatown, situated just to the north of South Central LA, was disproportionately damaged because of racial tensions between communities. Much of the blame for the extensive nature of the violence was attributed to LAPD Chief of Police Daryl Gates, who had already announced his resignation by the time of the riots, for failure to de-escalate the situation and overall mismanagement.[9][10]

Background

[edit]

Policing in Los Angeles

[edit]Before the release of the Rodney King videotape, minority community leaders in Los Angeles had repeatedly complained about harassment and use of excessive force against their residents by Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD) officers.[12] Daryl Gates, Chief of the LAPD from 1978 to 1992, has been blamed for the riots.[13][14] According to one study, "scandalous racist violence... marked the LAPD under Gates's tempestuous leadership."[15] Under Gates, the LAPD had begun Operation Hammer in April 1987, which was a large-scale militarized push in Los Angeles.

The origin of Operation Hammer can be traced to the 1984 Olympic Games held in Los Angeles. Under Gates's direction, the LAPD expanded gang sweeps for the duration of the Olympics. These were implemented across wide areas of the city but especially in South Central and East Los Angeles, areas of predominately minority residents. After the games were over, the city began to revive the use of earlier anti-trade union and anti-syndicalist laws in order to maintain the security policy started for the Olympic games. The police more frequently conducted mass arrests of African American youth. Citizen complaints against police brutality increased 33 percent in the period 1984–1989.[16]

By 1990 more than 50,000 people, mostly minority males, had been arrested in such raids.[17] Critics have stated that the operation was racially motivated because it used racial profiling, targeting African American and Mexican American youths.[18] The perception that police had targeted non-white citizens likely contributed to the anger that erupted in the 1992 riots.[19]

The Christopher Commission later concluded that a "significant number" of LAPD officers "repetitively use excessive force against the public and persistently ignore the written guidelines of the department regarding force". The biases related to race, gender, and sexual orientation were found to have regularly contributed to the LAPD's use of excessive force.[20] The commission's report called for the replacement of both Chief Daryl Gates and the civilian Police Commission.[20]

Tensions toward Koreans

[edit]In the year before the riots, 1991, there was growing resentment and violence between the African American and Korean American communities.[21] Racial tensions had been simmering for years between these groups. In 1989, the release of Spike Lee's film Do the Right Thing highlighted urban tensions between white people, black people, and Koreans over racism and economic inequality.[22] Many Korean shopkeepers were upset because they suspected shoplifting from their black customers and neighbors. Many black customers were angry because they routinely felt disrespected and humiliated by Korean store owners. Neither group fully understood the extent of the cultural differences and language barriers, which further fueled tensions.[23]

On March 16, 1991, a year before the Los Angeles riots, storekeeper Soon Ja Du shot and killed black ninth-grader Latasha Harlins after a physical altercation. Du was convicted of voluntary manslaughter and the jury recommended the maximum sentence of 16 years, but the judge, Joyce Karlin, decided against prison time and sentenced Du to five years of probation, 400 hours of community service, and a $500 fine instead.[24] Relations between the African American and Korean communities significantly worsened after this, and the former became increasingly mistrustful of the criminal justice system.[25] A state appeals court later unanimously upheld Judge Karlin's sentencing decision in April 1992, a week before the riots.[26]

The Los Angeles Times reported on several other significant incidents of violence between the communities at the time:

Other recent incidents involve the tragic events of May 25, 1991, where two employees at a liquor store near 35th Street and Central Avenue were shot. Both victims, who had recently immigrated from Korea, lost their lives after complying with the demands of a robber described by the police as an African American. Additionally, last Thursday, an African American man suspected of committing a robbery in an auto parts store on Manchester Avenue was fatally injured by his accomplice. The incident occurred when his accomplice accidentally discharged a shotgun round during a struggle with the Korean American owner of the shop. "This violence is deeply unsettling," stated store owner Park. "But sadly, who speaks up for these victims?"[27]

Rodney King incident

[edit]On the evening of March 3, 1991, Rodney King and two passengers were driving west on the Foothill Freeway (I-210) through the Sunland-Tujunga neighborhood of the San Fernando Valley.[28] The California Highway Patrol (CHP) attempted to initiate a traffic stop and a high-speed pursuit ensued with speeds estimated at up to 115 mph (185 km/h), before King eventually exited the freeway at Foothill Boulevard. The pursuit continued through residential neighborhoods of Lake View Terrace in San Fernando Valley before King stopped in front of the Hansen Dam recreation center. When King finally stopped, LAPD and CHP officers surrounded King's vehicle and married CHP officers Timothy and Melanie Singer arrested him and two other car occupants.[29]

After the two passengers were placed in the patrol car, five Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD) officers – Stacey Koon, Laurence Powell, Timothy Wind, Theodore Briseno, and Rolando Solano – surrounded King, who came out of the car last. None of the officers involved were African-American; officers Koon, Wind and Powell were Caucasian, while Briseno and Solano were of Hispanic origin.[30] They tasered King, struck him dozens of times with side-handled batons, kick-stomped him in his back and tackled him to the ground before handcuffing him and hogtying his legs. Sergeant Koon later testified at trial that King resisted arrest and that he believed King was under the influence of PCP at the time of the arrest, causing him to be aggressive and violent toward the officers.[31] Video footage of the arrest showed that King attempted to get up each time he was struck and that the police made no attempt to cuff him until he lay still.[32] A subsequent test of King for the presence of PCP in his body at the time of the arrest was negative.[33]

Unbeknownst to the police and King, the incident was captured on a camcorder by local civilian George Holliday from his nearby apartment across from Hansen Dam. The tape was roughly 12 minutes long. While the tape was presented during the trial, some clips of the incident were not released to the public.[34] In a later interview, King, who was on parole for a robbery conviction and had past convictions for assault, battery and robbery,[35][36] said he did not surrender earlier because he was driving while intoxicated, which he knew violated the terms of his parole.

The footage of King being beaten by police became an instant focus of media attention and a rallying point for activists in Los Angeles and around the United States. Coverage was extensive during the first two weeks after the incident: the Los Angeles Times published 43 articles about it,[37] The New York Times published 17 articles,[38] and the Chicago Tribune published 11 articles.[39] Eight stories appeared on ABC News, including a 60-minute special on Primetime Live.[40]

Upon watching the tape of the beating, LAPD chief of police Daryl Gates said:

I stared at the screen in disbelief. I played the one-minute-50-second tape again. Then again and again, until I had viewed it 25 times. And still I could not believe what I was looking at. To see my officers engage in what appeared to be excessive use of force, possibly criminally excessive, to see them beat a man with their batons 56 times, to see a sergeant on the scene who did nothing to seize control, was something I never dreamed I would witness.[41]

Charges and trial

[edit]The Los Angeles County District Attorney subsequently charged four police officers, including one sergeant, with assault and use of excessive force.[42] Due to the extensive media coverage of the arrest, the trial received a change of venue from Los Angeles County to Simi Valley in neighboring Ventura County.[43] The jury had no members who were entirely African American.[44] The jury was composed of nine white Americans (three women, six men), one biracial man,[45] one Latin American woman, and one Asian-American woman.[46] The prosecutor, Terry White, was black.[47][48]

On April 29, 1992, the seventh day of jury deliberations, the jury acquitted all four officers of assault and acquitted three of the four of using excessive force. The jury could not agree on a verdict for the fourth officer charged with using excessive force.[46] The verdicts were based in part on the first three seconds of a blurry, 13-second segment of the videotape that, according to journalist Lou Cannon, had not been aired by television news stations in their broadcasts.[49][50]

The first two seconds of videotape,[51] contrary to the claims made by the accused officers, show King attempting to flee past Laurence Powell. During the next one minute and 19 seconds, King is beaten continuously by the officers. The officers testified that they tried to restrain King before the videotape's starting point physically, but King could throw them off physically.[52]

Afterward, the prosecution suggested that the jurors may have acquitted the officers due to them becoming desensitized to the beating's violence, as the defense played the videotape repeatedly in slow motion, breaking it down until its emotional impact was lost.[53]

Outside the Simi Valley courthouse where the acquittals were delivered, county sheriff's deputies protected Stacey Koon from angry protesters on the way to his car. Movie director John Singleton, who was in the crowd at the courthouse, predicted, "By having this verdict, what these people done, they lit the fuse to a bomb."[54]

Events

[edit]The riots began the day the verdicts were announced and peaked in intensity over the next two days. A dusk-to-dawn curfew and deployment by the California National Guard, US troops, and federal law enforcement personnel eventually controlled the situation.[55]

A total of 63 people died during the riots, including nine shot by police and one by the National Guard.[56] Of those killed during the riots, 2 were Asian, 28 were black, 19 were Latino, and 14 were white. No law enforcement officials died during the riots.[57] As many as 2,383 people were reported injured.[58] Estimates of the material losses vary between about $800 million and $1 billion.[59] Approximately 3,600 fires were set, destroying 1,100 buildings, with fire calls coming once every minute at some points. Widespread looting also occurred. Rioters targeted stores owned by Koreans and other ethnic Asians, reflecting tensions between them and the African American communities.[60]

Many of the disturbances were concentrated in South Central Los Angeles, where the population was majority African American and Hispanic. Fewer than half of all the riot arrests and a third of those killed during the violence were Hispanic.[61][62]

The riots caused the Emergency Broadcast System to be activated on April 30, 1992, on KCAL-TV and KTLA, the first time in the city's history (not counting the test activation).[63]

Day 1 – Wednesday, April 29

[edit]Prior to the verdicts

[edit]In the week before the Rodney King verdicts were reached, Los Angeles Police Chief Daryl Gates set aside $1 million for possible police overtime. Even so, on the last day of the trial, two-thirds of the LAPD's patrol captains were out of town in Ventura, California, on the first day of a three-day training seminar.[64]

At 1 p.m. on April 29, Judge Stanley Weisberg announced that the jury had reached its verdict, which would be read in two hours' time. This was done to allow reporters and police and other emergency responders to prepare for the outcome, as unrest was feared if the officers were acquitted.[64] The LAPD had activated its Emergency Operations Center, which the Webster Commission described as "the doors were opened, the lights turned on and the coffee pot plugged in", but taken no other preparatory action. Specifically, the people intended to staff that Center were not gathered until 4:45 p.m. In addition, no action was taken to retain extra personnel at the LAPD's shift change at 3 p.m., as the risk of trouble was deemed low.[64]

Verdicts announced

[edit]The acquittals of the four accused Los Angeles Police Department officers came at 3:15 p.m. local time. By 3:45 p.m., a crowd of more than 300 people had appeared at the Los Angeles County Courthouse protesting the verdicts.[citation needed]

Meanwhile, at approximately 4:15–4:20 p.m., a group of people approached the Pay-Less Liquor and Deli on Florence Avenue just west of Normandie in South Central. In an interview, a member of the group said that the group "just decided they weren't going to pay for what they were getting". The store owner's son was hit with a beer bottle, and two other youths smashed the store's glass front door. Two officers from the 77th Street Division of the LAPD responded to this incident and, finding that the instigators had already left, completed a report.[65][66]

Mayor Bradley speaks

[edit]At 4:58 p.m.,[67] Los Angeles Mayor Tom Bradley held a news conference to discuss the verdicts. He both expressed anger about the verdicts and appealed for calm.[53]

"Today, this jury told the world that what we all saw with our own eyes wasn't a crime. Today, that jury asked us to accept the senseless and brutal beating of a helpless man. Today, that jury said we should tolerate such conduct by those sworn to protect and serve. My friends, I am here to tell this jury, "No. No, our eyes did not deceive us. We saw what we saw, what we saw was a crime..." We must not endanger the reforms we have achieved by resorting to mindless acts. We must not push back progress by striking back blindly."

— Los Angeles Mayor Tom Bradley, post-verdict press conference

Assistant Los Angeles police chief Bob Vernon later said he believed Bradley's remarks incited a riot and were perhaps taken as a signal by some citizens. Vernon said that the number of police incidents rose in the hour after the mayor's press conference.[53]

Police intervention at 71st and Normandie

[edit]At Florence and Halldale, two officers issued a plea for assistance in apprehending a young suspect who had thrown an object at their car and whom they were pursuing on foot.[68] Approximately two dozen officers, commanded by 77th Street Division LAPD Lieutenant Michael Moulin, arrived and arrested the youth, 16-year old Seandel Daniels, forcing him into the back of a car. The rough handling of the young man, a well-known minor in the community, further agitated an uneasy and growing crowd, who began taunting and berating the police.[69] Among the crowd were Bart Bartholomew, a white freelance photographer for The New York Times, and Timothy Goldman, a black US Air Force veteran [70][71] who began to record the events with his personal camcorder.[72][70]

The police formed a perimeter around the arresting officers as the crowd grew more hostile, leading to further altercations and arrests (including that of Damian Williams' older brother, Mark Jackson). One member of the crowd stole the flashlight of an LAPD officer. Fearing police would resort to deadly force to repel the growing crowd, Lieutenant Moulin ordered officers out of the area altogether. Moulin later said that officers on the scene were outnumbered and unprepared to handle the situation because their riot equipment was stored at the police academy.[citation needed]

Hey, forget the flashlight, it's not worth it. It ain't worth it. It's not worth it. Forget the flashlight. Not worth it. Let's go.

— Lieutenant Michael Moulin, bullhorn broadcast as recorded by the Goldman footage at 71st and Normandie[73]

Moulin made the call for reporting officers to retreat from the 71st and Normandie area entirely at approximately 5:50 p.m.[11][65] They were sent to an RTD bus depot at 54th and Arlington[74] and told to await further instructions. The command post formed at this location was set up at approximately 6 p.m, but had no cell phones or computers other than those in squad cars. It had insufficient numbers of telephone lines and handheld police radios to assess and respond to the situation.[74] Finally, the site had no televisions, which meant that as live broadcasts of unrest began, command post officers could not see any of the coverage.[75]

Unrest moves to Florence and Normandie

[edit]After the retreat of officers at 71st and Normandie, many proceeded one block south to the intersection of Florence and Normandie.[76] As the crowd began to turn physically dangerous, Bartholomew managed to flee the scene with the help of Goldman. Someone hit Bartholomew with a wood plank, breaking his jaw, while others pounded him and grabbed his camera.[70] Just after 6 p.m., a group of young men broke the padlock and windows to Tom's Liquor, allowing a group of more than 100 people to raid the store and loot it.[77] Concurrently, the growing number of rioters in the street began attacking civilians of non-black appearance, throwing debris at their cars, pulling them from their vehicles when they stopped, smashing window shops, or assaulting them while they walked on the sidewalks. As Goldman continued to film the scene on the ground with his camcorder, the Los Angeles News Service team of Marika Gerrard and Zoey Tur arrived in a news helicopter, broadcasting from the air. The LANS feed appeared live on numerous Los Angeles television venues.[78]

At approximately 6:15 p.m., as reports of vandalism, looting, and physical attacks continued to come in, Moulin elected to "take the information" but not to respond or send personnel to restore order or rescue people in the area.[68] Moulin was relieved by a captain, ordered only to assess the Florence and Normandie area, and, again, not to attempt to deploy officers there.[79] Meanwhile, Tur continued to cover the events in progress live at the intersection. From overhead, Tur described the police presence at the scene around 6:30 p.m. as "none".[80]

Attack on Larry Tarvin

[edit]At 6:43 p.m., a white truck driver, Larry Tarvin, drove down Florence and stopped at a red light at Normandie in a large white delivery truck. With no radio in his truck, he did not know that he was driving into a riot.[81] Tarvin was pulled from the vehicle by a group of men including Henry Watson, who proceeded to kick and beat him, before striking him unconscious with a fire extinguisher taken from his own vehicle.[82] He lay unconscious for more than a minute[80] as his truck was looted, before getting up and staggering back to his vehicle. With the help of an unknown African American, Tarvin drove his truck out of further harm's way.[81][75] Just before he did so, another truck, driven by Reginald Denny, entered the intersection.[81] United Press International Radio Network reporter Bob Brill, who was filming the attack on Tarvin, was hit in the head with a bottle and stomped on.[83]

Attack on Reginald Denny

[edit]

Reginald Denny, a white construction truck driver, was pulled from his truck and severely beaten by a group of black men who came to be known as the "LA Four". The attack was recorded on video from Tur's and Gerrard's news helicopter, and broadcast live on US national television. Goldman captured the end of the attack and a close-up of Denny's bloody face.[84]

As the LA Four fled, another quartet of black residents came to Denny's aid, placing him back in his truck, in which one of the rescuers drove him to the hospital. Denny suffered a fractured skull and impairment of his speech and ability to walk, for which he underwent years of rehabilitative therapy. After unsuccessfully suing the City of Los Angeles, Denny moved to Arizona, where he worked as an independent boat mechanic and has mostly avoided media contact.[85]

Attack on Fidel Lopez

[edit]Around 7:40 p.m., almost an hour after Denny was rescued, another beating was filmed on videotape in that location. Fidel Lopez, a self-employed construction worker and Guatemalan, was pulled from his GMC pickup truck and robbed of $2,000 (equivalent to $4,400 in 2023[86]).[87] Rioters, including Damian Williams, smashed his forehead open with a car stereo[88] and one tried to slice his ear off.[89] After Lopez lost consciousness, the crowd spray-painted his chest, torso, and genitals black.[90] He was eventually rescued by black Reverend Bennie Newton, who told the rioters: "Kill him, and you have to kill me too."[89][91] Lopez survived the attack, but it took him years to fully recover and re-establish his business. Newton and Lopez became close friends.[92] In 1993, Reverend Benny Newton died of leukemia.

Sunset on the first evening of the riots was at 7:36 p.m.[93] The first call reporting a fire came in soon after, at approximately 7:45 p.m.[94] Police did not return in force to Florence and Normandie until 8:30 p.m.[66]

Numerous factors were later blamed for the severity of rioting in the 77th Street Division on the evening of April 29. These included:[75]

- No effort made to close the busy intersection of Florence and Normandie to traffic.

- Failure to secure gun stores in the Division (one in particular lost 1,150 guns to looting on April 29).

- The failure to issue a citywide Tactical Alert until 6:43 p.m., which delayed the arrival of other divisions to assist the 77th.

- The lack of any response – and in particular, a riot response – to the intersection, which emboldened rioters. Since attacks, looting, and arson were broadcast live, viewers could see that none of these actions were being stopped by police.

Parker Center

[edit]As noted, after the verdicts were announced, a crowd of protesters formed at the Los Angeles police headquarters at Parker Center in Downtown Los Angeles. The crowd grew as the afternoon passed and became violent. The police formed a skirmish line to protect the building, sometimes moving back in the headquarters as protesters advanced, attempting to set the Parker Center ablaze.[95] In the midst of this, before 6:30 p.m., police chief Daryl Gates left Parker Center, on his way to the neighborhood of Brentwood. There, as the situation in Los Angeles deteriorated, Gates attended a political fundraiser against Los Angeles City Charter Amendment F,[95] intended to "give City Hall more power over the police chief and provide more civilian review of officer misconduct".[96] The amendment would limit the power and term length of his office.[97]

The Parker Center crowd grew riotous at approximately 9 p.m.,[94] eventually making their way through the Civic Center, attacking law enforcement, overturning vehicles, setting objects ablaze, vandalizing government buildings and blocking traffic on US Route 101 going through other nearby districts in downtown Los Angeles looting and burning stores. Nearby Los Angeles Fire Department (LAFD) firefighters were shot at while trying to put out a blaze set by looters. The mayor had requested the California Army National Guard from Governor Pete Wilson; the first of these units, the 670th Military Police Company, had traveled almost 300 miles (480 km) from its main armory and arrived in the afternoon to assist local police.[citation needed]

Lake View Terrace

[edit]In the Lake View Terrace district of Los Angeles, 200[94]–400[75] protesters gathered about 9:15 p.m. at the site where Rodney King was beaten in 1991, near the Hansen Dam Recreation Area. The group marched south on Osborne Street to the LAPD Foothill Division headquarters.[94] There they began rock throwing, shooting into the air, and setting fires. The Foothill division police used riot-breaking techniques to disperse the crowd and arrest those responsible for rock throwing and the fires[75] eventually leading to rioting and looting in the neighboring area of Pacoima and its surrounding neighborhoods in the San Fernando Valley.

Day 2 – Thursday, April 30

[edit]Mayor Bradley signed an order for a dusk-to-dawn curfew at 12:15 a.m. for the core area affected by the riots, as well as declaring a state of emergency for the city of Los Angeles. At 10:15 a.m., he expanded the area under curfew.[94] By mid-morning, violence appeared widespread and unchecked as extensive looting and arson were witnessed across Los Angeles County. Rioting moved from South Central Los Angeles, going north through Central Los Angeles causing widespread destruction in the neighborhoods of Koreatown, Westlake, Pico-Union, Echo Park, Hancock Park, Fairfax, Mid-City and Mid-Wilshire before reaching Hollywood. The looting and fires engulfed Hollywood Boulevard, and simultaneously rioting moved west and south into the neighboring independent cities of Inglewood, Hawthorne, Gardena, Compton, Carson and Long Beach, as well as moving east from South Central Los Angeles into the cities of Huntington Park, Walnut Park, South Gate and Lynwood and Paramount. Looting and vandalism had also gone as far south as Los Angeles regions of the Harbor Area in the neighborhoods of San Pedro, Wilmington, and Harbor City.[citation needed]

Destruction of Koreatown

[edit]Koreatown is a roughly 2.7 square-mile (7 square kilometer) neighborhood between Hoover Street and Western Avenue, and 3rd Street and Olympic Boulevard, west of MacArthur Park and east of Hancock Park/Windsor Square.[98] Korean immigrants had begun settling in the Mid-Wilshire area in the 1960s after the passage of the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965. It was here that many opened successful businesses.[99]

As the riots spread, roads between Koreatown and wealthy white neighborhoods were blocked off by police and official defense lines were set up around the independent cities such as Beverly Hills and West Hollywood, as well as middle-upper class white neighborhoods west of Robertson Boulevard in Los Angeles.[100] A Korean American resident later told reporters: "It was containment. The police cut off Koreatown traffic, while we were trapped on the other side without help. Those roads are a gateway to a richer neighborhood. It can't be denied."[101] Some Koreans later said they did not expect law enforcement to come to their aid.[102]

The lack of law enforcement forced Koreatown civilians to organize their own armed security teams, mainly composed of store owners, to defend their businesses from rioters.[101] Those who stood on the roof of the California Supermarket at 5th and Western Avenue with firearms were later referred to as the "roof" or "rooftop Koreans". Many had military experience from serving in the Republic of Korea Armed Forces before emigrating to the United States.[103] Open gun battles were televised, including an incident in which Korean shopkeepers armed with M1 carbines, Ruger Mini-14s, pump-action shotguns, and handguns exchanged gunfire with a group of armed looters, and forced their retreat.[104] But there were casualties, such as 18-year-old Edward Song Lee, whose body can be seen lying in the street in images taken by photojournalist Hyungwon Kang.[102]

After events in Koreatown, the 670th MP Company from National City, California were redeployed to reinforce police patrols guarding the Korean Cultural Center and the Consulate-General of South Korea in Los Angeles.[105]

Out of the $850 million worth of damage done in LA, half of it was on Korean-owned businesses.[106]

Mid-town containment

[edit]The LAPD and the Los Angeles County Sheriff's Department (LASD) organized response began to come together by midday. The LAFD and Los Angeles County Fire Department (LACoFD) began to respond backed by police escort; California Highway Patrol reinforcements were airlifted to the city. US President George H. W. Bush spoke out against the rioting, saying anarchy would not be tolerated. The California Army National Guard, which had been advised not to expect civil disturbance and had, as a result, loaned its riot equipment out to other law enforcement agencies, responded quickly by calling up about 2,000 soldiers, but could not get them to the city until nearly 24 hours had passed. They lacked equipment and had to pick it up from the JFTB (Joint Forces Training Base), Los Alamitos, California, which at the time was mainly a mothballed former airbase.[107]

Air traffic control procedures at Los Angeles International Airport were modified, with all departures and arrivals routed to and from the west, over the Pacific Ocean, avoiding overflights of neighborhoods affected by the rioting.[citation needed]

Bill Cosby spoke on the local television station KNBC and asked people to stop the rioting and watch the final episode of his The Cosby Show.[108][109][110] The US Justice Department announced it would resume federal investigation of the Rodney King beating as a violation of federal civil rights law.[94]

Day 3 – Friday, May 1

[edit]In the early morning hours of Friday, May 1, the major rioting was stopped.[111] Rodney King gave an impromptu news conference in front of his lawyer's office, tearfully saying, "People, I just want to say, you know, can we all get along?"[112][113] That morning, at 1:00 am, Governor Wilson had requested federal assistance. Upon request, Bush invoked the Insurrection Act with Executive Order 12804, federalizing the California Army National Guard and authorizing federal troops and federal law enforcement officers to help restore law and order.[citation needed] With Bush's authority, the Pentagon activated Operation Garden Plot, placing the California Army National Guard and federal troops under the newly formed Joint Task Force Los Angeles (JTF-LA). The deployment of federal troops was not ready until Saturday, by which time the rioting and looting were under control.

Meanwhile, the 40th Infantry Division (doubled to 4,000 troops) of the California Army National Guard continued to move into the city in Humvees; eventually 10,000 Army National Guard troops were activated. That same day, 1,000 federal tactical officers from different agencies across California were dispatched to L.A. to protect federal facilities and assist local police. Later that evening, Bush addressed the country, denouncing "random terror and lawlessness". He summarized his discussions with Mayor Bradley and Governor Wilson and outlined the federal assistance he was making available to local authorities. Citing the "urgent need to restore order", he warned that the "brutality of a mob" would not be tolerated, and he would "use whatever force is necessary". He referred to the Rodney King case, describing talking to his own grandchildren and noting the actions of "good and decent policemen" as well as civil rights leaders. He said he had directed the Justice Department to investigate the King case, and that "grand jury action is underway today", and justice would prevail. The Post Office announced that it was unsafe for their couriers to deliver mail. The public were instructed to pick up their mail at the main Post Office. The lines were approximately 40 blocks long, and the California National Guard were diverted to that location to ensure peace.[114]

By this point, many entertainments and sports events were postponed or canceled. The Los Angeles Lakers hosted the Portland Trail Blazers in an NBA playoff basketball game on the night the rioting started. The following game was postponed until Sunday and moved to Las Vegas. The Los Angeles Clippers moved a playoff game against the Utah Jazz to nearby Anaheim. In baseball, the Los Angeles Dodgers postponed games for four straight days from Thursday to Sunday, including a whole three-game series against the Montreal Expos; all were made up as part of doubleheaders in July. In San Francisco, a city curfew due to unrest forced the postponement of a May 1, San Francisco Giants home game against the Philadelphia Phillies.[115]

The horse racing venues Hollywood Park Racetrack and Los Alamitos Race Course were also shut down. LA Fiesta Broadway, a major event in the Latino community, was canceled. In music, Van Halen canceled two concert shows in Inglewood on Saturday and Sunday. Metallica and Guns N' Roses were forced to postpone and relocate their concert to the Rose Bowl as the LA Coliseum and its surrounding neighborhood were still damaged. Michael Bolton canceled his scheduled performance at the Hollywood Bowl Sunday. The World Wrestling Federation canceled events on Friday and Saturday in the cities of Long Beach and Fresno.[116] By the end of Friday night, all the remaining smaller riots were completely quelled.[111]

Day 4 – Saturday, May 2

[edit]On the fourth day, 3,500 federal troops – 2,000 soldiers of the 7th Infantry Division from Fort Ord and 1,500 Marines of the 1st Marine Division from Camp Pendleton – arrived to reinforce the National Guard soldiers already in the city. The Marine Corps contingent included the 1st Light Armored Reconnaissance Battalion, commanded by John F. Kelly. It was the first significant military occupation of Los Angeles by federal troops since the 1894 Pullman Strike,[117] and also the first federal military intervention in an American city to quell a civil disorder since the 1968 King assassination riots, and the deadliest modern unrest since the 1980 Miami riots at the time, only 12 years earlier.[citation needed]

These federal military forces took 24 hours to deploy to Huntington Park, about the same time it took for the National Guard.[citation needed] This brought total troop strength to 13,500, making LA the largest military occupation of any US city since the 1968 Washington, D.C. riots. Federal troops joined National Guard soldiers to support local police in restoring order directly; the combined force contributed significantly to preventing violence.[citation needed] With most of the violence under control, 30,000 people attended an 11 a.m. peace rally in Koreatown to support local merchants and racial healing.[94]

Day 5 – Sunday, May 3

[edit]

Mayor Bradley assured the public that the crisis was, more or less, under control as areas became quiet.[118] Later that night, Army National Guard soldiers shot and killed a motorist who tried to run them over at a barrier.[119]

In another incident, the LAPD and Marines intervened in a domestic dispute in Compton, in which the suspect held his wife and children hostage. As the officers approached, the suspect fired two shotgun rounds through the door, injuring some of the officers. One of the officers yelled to the Marines, "Cover me," as per law enforcement training to be prepared to fire if necessary. However, per their military training, the Marines interpreted the wording as providing cover by establishing a base of firepower, resulting in a total of 200 rounds being sprayed into the house. Remarkably, neither the suspect nor the woman and children inside the house were harmed.[120]

Aftermath

[edit]Although Mayor Bradley lifted the curfew, signaling the official end of the riots, sporadic violence and crime continued for a few days afterward. Schools, banks, and businesses reopened. Federal troops did not stand down until May 9. The Army National Guard remained until May 14. Some National Guard soldiers remained as late as May 27.[121]

Involvement

[edit]Korean Americans

[edit]Many Korean Americans in Los Angeles refer to the event as 'Sa-I-Gu', meaning "four-two-nine" in the Korean language (4.29), in reference to April 29, 1992, which was the day the riots started. Over 2,300 mom-and-pop shops run by Korean business owners were damaged through ransacking and looting during the riots, sustaining close to $400 million in damages.[122]

During the riots, Korean Americans received very little aid or protection from police authorities, due to their low social status and language barriers.[123] Many Koreans rushed to Koreatown after Korean-language radio stations called for volunteers to guard against rioters. Many of the volunteers that helped defend the Korean stores were from an organization called LA Korean Youth Task Force and they went to protect these stores because there were no adult males in those families that could do it.[124] Many were armed, with a variety of improvised weapons, handguns, shotguns, and semi-automatic rifles.[125]

Television coverage of two Korean merchants firing pistols repeatedly at roving looters was widely seen and controversial. The New York Times said: "that the image seemed to speak of race war, and of vigilantes taking the law into their own hands."[126] One of the merchants, David Joo, said, "I want to make it clear that we didn't open fire first. At that time, four police cars were there. Somebody started to shoot at us. The LAPD ran away in half a second. I never saw such a fast escape. I was pretty disappointed." Carl Rhyu, also a participant in the Koreans' armed response, said, "If it was your own business and your own property, would you be willing to trust it to someone else? We are glad the National Guard is here. They're good backup. But when our shops were burning we called the police every five minutes; no response."[126] At a shopping center several miles north of Koreatown, Jay Rhee, who said he and others fired five hundred shots into the ground and air, said, "We have lost our faith in the police. Where were you when we needed you?" Despite Koreatown's relative geographical isolation from South Central Los Angeles, it was the most severely damaged in the riots.[123]

The riots have been considered a major turning point in the development of a distinct Korean American identity and community. Korean Americans responded in various ways, including the development of new ethnic agendas and organization and increased political activism.

Preparations ahead of the 1993 verdict

[edit]One of the largest armed camps in Los Angeles's Koreatown congregated at the California Market. On the first night after the officers' verdicts were returned, Richard Rhee, the market owner, set up camp in the parking lot with about 20 armed employees.[127] One year after the riots, fewer than one in four damaged or destroyed businesses had reopened, according to the survey conducted by the Korean American Inter-Agency Council.[128] According to a Los Angeles Times survey conducted eleven months after the riots, almost 40 percent of Korean Americans said they were thinking of leaving Los Angeles.[129]

Before a verdict was issued in the new 1993 Rodney King federal civil rights trial against the four officers, many Korean shop owners prepared for violence. Gun sales increased sharply, many to people of Korean descent; some merchants at flea markets removed merchandise from shelves, and they fortified storefronts with extra Plexiglas and bars. Throughout the region, merchants readied to defend themselves, and others formed armed militia groups.[128] College student Elizabeth Hwang spoke of the attacks on her parents' convenience store in 1992. She said at the time of the 1993 trial, they had been armed with a Glock 17 pistol, a Beretta, and a shotgun, and they planned to barricade themselves in their store to fight off looters.[128]

Aftermath

[edit]

About 2,300 Korean-owned stores in southern California were looted or burned, making up 45 percent of all damages caused by the riot. According to the Asian and Pacific American Counseling and Prevention Center, 730 Koreans were treated for post-traumatic stress disorder, which included insomnia and a sense of helplessness and muscle pain. In reaction, many Korean Americans worked to create political and social empowerment.[123]

As a result of the LA riots, Korean Americans formed activist organizations such as the Association of Korean American Victims. They built collaborative links with other ethnic groups through groups like the Korean American Coalition.[130] A week after the riots, in the largest Asian American protest ever held in a city, about 30,000 mostly-Korean and Korean American marchers walked the streets of LA Koreatown, calling for peace and denouncing violence. This cultural movement was devoted to the protection of Koreans' political rights, ethnic heritage, and political representation. New leaders arose within the community, and second-generation children spoke on behalf of the community. Korean Americans began to have different occupation goals, from store-owners to political leaders. Korean Americans worked to gain governmental aid to rebuild their damaged neighborhoods. Countless community and advocacy groups have been established to further fuel Korean political representation and understanding.[123]

Edward Taehan Chang, a professor of ethnic studies and founding director of the Young Oak Kim Center for Korean American Studies at the University of California, Riverside, has identified the LA riots as a turning point for the development of a Korean American identity separate from that of Korean immigrants and that was more politically active. "What was an immigrant Korean identity began to shift. The Korean American identity was born ... They learned a valuable lesson that we have to become much more engaged and politically involved and that political empowerment is very much part of the Korean American future."[citation needed]

According to Edward Park, the 1992 violence stimulated a new wave of political activism among Korean Americans, but it also split them into two camps.[131][132] The liberals sought to unite with other minorities in Los Angeles to fight against racial oppression and scapegoating. The conservatives emphasized law and order and generally favored the economic and social policies of the Republican Party. The conservatives tended to emphasize the differences between Koreans and other minorities, specifically African Americans.[133][134]

Latinos

[edit]According to a 1993 report by the Latinos Futures Research Group for the Latino Coalition for a New Los Angeles, one-third of those who were killed and one half of those who were arrested in the riots were Latino; between 20 and 40 percent of the businesses that were looted were owned by Latinos.[135] Hispanics were considered a minority despite their increasing numbers, so they lacked political support and were poorly represented. This lack of social and political representation obscured acknowledgment of their participation in the riots. Many who lived in the area were new immigrants, not yet able to speak English.[136]

According to Gloria Alvarez, the riots united Hispanics and black people instead of driving them apart. Although the riots were viewed as having different aspects, Alvarez writes that they contributed to greater understanding between Hispanics and blacks. Hispanics now heavily populate the once-predominantly-black area, and the relationship between Hispanics and blacks has improved. Building a stronger and more-understanding community could help prevent outbreaks of social chaos,[137] although hate crimes and widespread violence between the two groups continue to be a problem in the Los Angeles area.[138]

Media coverage

[edit]

Almost as soon as the disturbances broke out in South Central, local television news cameras were on the scene to record the events as they happened.[139] Television coverage of the riots was near-continuous, starting with the beating of motorists at the intersection of Florence and Normandie which was broadcast live by television news pilot and reporter Zoey Tur and her camera operator Marika Gerrard.[140][141]

In part because of extensive media coverage of the Los Angeles riots, smaller but similar riots and other anti-police actions took place in other cities throughout the United States.[142][143] The Emergency Broadcast System was also utilized during the rioting.[144]

Another prominent source of media coverage was Korea Times, an independent Korean American newspaper.

The Korea Times

[edit]Richard Reyes Fruto wrote in an article in The Korea Times, "Looters targeted Korean American merchants during the L.A. Riots, according to the FBI official who directed federal law enforcement efforts during the disturbance."[145] The English-language Korean newspaper focused on the 1992 riots, with Korean Americans at the center of the violence. Initial articles in late April and early May described victims' lives and damage to the Los Angeles Korean community. Interviews with Koreatown merchants such as Chung Lee evoked sympathy from readers. Lee watched, helpless, as his store was burned down: "I worked hard for that store. Now I have nothing".[145]

Mainstream media

[edit]While several articles included the minorities who were involved when damages were cited or victims were named, few of them actually incorporated them as a significant aspect of the struggle. One story framed the race riots as occurring at a "time when the wrath of blacks was focused on whites".[146] They acknowledged the fact that racism and stereotyped views contributed to the riots; articles in American newspapers portrayed the LA riots as an incident that erupted between black and white people who were struggling to coexist with each other, rather than include all of the minority groups that were involved in the riots.[147]

On Nightline, Ted Koppel initially only interviewed black leaders about the black/Korean conflict,[148] and they shared detrimental opinions about Korean Americans.[149]

Activist Guy Aoki became frustrated with early coverage because only black/White framing was used in it, the Korean American community and the suffering which it experienced were vilified and ignored.[149]

Some felt that too much emphasis was placed on the suffering of Korean Americans. As filmmaker Dai Sil Kim-Gibson, who produced the 1993 documentary Sa-I-Gu, described, "black-Korean conflict was one symptom, but it was certainly not the cause of that riot. The cause of that riot was the black-white conflict that existed in this country from the establishment of this country."[150]

In an NBC News article written by Hanna Kang, she sees the conflict between Korean Americans and blacks as overstated and only part of the story was told in the news. In this article, Kang interviews more than twenty people from both races in many different fields, and all of them had the same view of the media during the riots. They all believe the influence of the new coverage persuaded how the public looked at the riots. She goes on to say that many of the pictures that were shown in the media coverage of Korean Americans, were pictures of them standing on the tops of the buildings defending them. This was only a small portion of the store owners who could do this. With these misunderstandings between the two races, many believe that education is the only way to get rid of these conflicts in the future.[151]

Aftermath

[edit]

After the riots subsided, an inquiry was commissioned by the city Police Commission, led by William H. Webster (special advisor), and Hubert Williams (deputy special advisor, president of the Police Foundation).[152] The findings of the inquiry, The City in Crisis: A Report by the Special Advisor to the Board of Police Commissioners on the Civil Disorder in Los Angeles, also colloquially known as the Webster Report or Webster Commission, was released on October 21, 1992.[153][relevant?]

LAPD chief of police Daryl Gates, who had seen his successor Willie L. Williams named by the Police Commission days before the riots,[154] was forced to resign on June 28, 1992.[155] Some areas of the city saw temporary truces between the rival Crips and Bloods gangs, as well as between rival Latino gangs, which fueled speculation among LAPD officers that the truce was going to be used to unite the gangs against the department.[156]

Post-riot commentary

[edit]Scholars and writers

[edit]In addition to the catalyst of the verdicts in the excessive force trial, various other factors have been cited as causes of the unrest. In the years preceding the riots, several other highly controversial incidents involving police brutality or other perceived injustices against minorities had been criticized by activists and investigated by the media. Thirteen days after the beating of King was widely broadcast, black people were outraged when Latasha Harlins, a 15-year-old black girl, was fatally shot in the back of the head by a Korean American shopkeeper, Soon Ja Du, in the course of an assumed shoplifting incident and brief physical altercation. Though the jury recommended a sentence of 16 years, Judge Joyce Karlin changed the sentence to just five years of probation and 400 hours of community service–and no jail time.[157]

Rioters targeted Korean American shops in their areas, as there had been considerable tension between the two communities. Such sources as Newsweek and Time suggested that black people thought Korean American merchants were "taking money out of their community", that they were racist as they refused to hire black people, and often treated them without respect. There were cultural and language differences, as some shop owners were immigrants.[158][159]

There were other factors for social tensions: high rates of poverty and unemployment among the residents of South Central Los Angeles, which had been deeply affected by the nationwide recession.[160][161] Articles in the Los Angeles Times and The New York Times linked the economic deterioration of South Central to the declining living conditions of the residents, and reported that local resentments about these conditions helped to fuel the riots.[162][163][164][165][166] Other scholars compare these riots to those in Detroit in the 1920s when the whites rioted against black people.[citation needed] But instead of African Americans as victims, the race riots "represent backlash violence in response to recent Latino and Asian immigration into African American neighborhoods".[6]

Social commentator Mike Davis points to the growing economic disparity in Los Angeles, caused by corporate restructuring and government deregulation, with inner-city residents bearing the brunt of such changes; such conditions engendered a widespread feeling of frustration and powerlessness in the urban populace, who reacted to the King verdicts with a violent expression of collective public protest.[167][168] To Davis and other writers, the tensions between African Americans and Korean Americans had as much to do with the economic competition between the two groups caused by wider market forces as with cultural misunderstandings and black anger about the killing of Latasha Harlins.[62]

Davis wrote that the 1992 Los Angeles Riots were still remembered over 20 years later and that not many changes had yet occurred; conditions of economic inequality, lack of jobs available for black and Latino youth, and civil liberty violations by law enforcement had remained largely unaddressed years later. Davis described this as a "conspiracy of silence", especially in view of statements made by the Los Angeles Police Department that they would make reforms coming to little fruition. Davis argued that the rioting was different from in the 1965 Watts Riots, which had been more unified among all minorities living in Watts and South Central; the 1992 riots, on the other hand, were characterized by divided uproars that defied description of a simple uprising of black against white and involved the destruction and looting of many businesses owned by racial minorities.[169]

A Special Committee of the California Legislature also studied the riots, producing a report entitled To Rebuild is Not Enough.[170] The Committee concluded that the inner-city conditions of poverty, racial segregation, lack of educational and employment opportunities, police abuse and unequal consumer services created the underlying causes of the riots. It also noted that the decline of industrial jobs in the American economy and the growing ethnic diversity of Los Angeles had contributed to urban problems. Another official report, The City in Crisis, was initiated by the Los Angeles Board of Police Commissioners; it made many of the same observations as the Assembly Special Committee about the growth of popular urban dissatisfaction.[171] In their study, Farrell and Johnson found similar factors, including the diversification of the L.A. population, the tension between the successful Korean businesses and other minorities, and excessive force on minorities by LAPD and the effect of laissez-faire business on urban employment opportunities.[172]

Rioters were believed to have been motivated by racial tensions but these are considered one of numerous factors.[173] Urban sociologist Joel Kotkin said, "This wasn't a race riot, it was a class riot."[158] Many ethnic groups participated in rioting, not only African Americans. Newsweek reported that "Hispanics and even some whites; men, women, and children mingled with African Americans."[158] When residents who lived near Florence and Normandie were asked why they believed riots had occurred in their neighborhoods, they responded to the perceived racist attitudes they had felt throughout their lifetime and empathized with the bitterness the rioters felt.[174] Residents who had respectable jobs, homes, and material items still felt like second class citizens.[174] A poll by Newsweek asked whether black people charged with crimes were treated more harshly or more leniently than other ethnicities; 75% of black people responded "more harshly", versus 46% of white people.[158]

In his public statements during the riots, Jesse Jackson, civil rights leader, sympathized with African Americans' anger about the verdicts in the King trial and noted the root causes of the disturbances. He repeatedly emphasized the continuing patterns of racism, police brutality, and economic despair suffered by inner-city residents.[175][176]

Several prominent writers expressed a similar "culture of poverty" argument. Writers in Newsweek, for example, drew a distinction between the actions of the rioters in 1992 with those of the urban upheavals in the 1960s, arguing that "[w]here the looting at Watts had been desperate, angry, mean, the mood this time was closer to a manic fiesta, a TV game show with every looter a winner."[158]

According to a 2019 study in the American Political Science Review found that the riots caused a liberal shift, both in the short-term and long-term, politically.[177]

The 1992 events in Los Angeles were compared to the May 2020 police murder of George Floyd in the US city of Minneapolis that resulted in a global protest movement against police brutality and structural racism.[178] Floyd's murder served as an inflection point after the police killing of Breonna Taylor in Louisville, Kentucky in March 2020, fueling cumulative public outrage. Unlike in 1992, participants who protested Floyd's murder were more racially diverse than in 1992 and there was little if any racially motivated violence.[179][180]

Politicians

[edit]Democratic presidential candidate Bill Clinton said that the violence resulted from the breakdown of economic opportunities and social institutions in the inner city. He also berated both major political parties for failing to address urban issues, especially the Republican Administration for its presiding over "more than a decade of urban decay" generated by their spending cuts.[181] He also maintained that the King verdicts could not be avenged by the "savage behavior" of "lawless vandals" and stated that people "are looting because ... [t]hey do not share our values, and their children are growing up in a culture alien from ours, without family, without neighborhood, without church, without support."[181] While Los Angeles was mostly unaffected by the urban decay the other metropolitan areas of the nation faced since the 1960s, racial tensions had been present since the late 1970s, becoming increasingly violent as the 1980s progressed.[citation needed]

Democrat Maxine Waters, the African American Congressional representative of South Central Los Angeles, said that the events in Los Angeles constituted a "rebellion" or "insurrection," caused by the underlying reality of poverty and despair existing in the inner city. This state of affairs, she asserted, was brought about by a government that had all but abandoned the poor and failed to help compensate for the loss of local jobs and the institutional discrimination encountered by racial minorities, especially at the police's hands and financial institutions.[182][183]

Conversely, President Bush argued that the unrest was "purely criminal". Though he acknowledged that the King verdicts were plainly unjust, he said that "we simply cannot condone violence as a way of changing the system ... Mob brutality, the total loss of respect for human life was sickeningly sad ... What we saw last night and the night before in Los Angeles is not about civil rights. It's not about the great cause of equality that all Americans must uphold. It's not a message of protest. It's been the brutality of a mob, pure and simple."[184]

Vice President Dan Quayle blamed the violence on a "Poverty of Values" – "I believe the lawless social anarchy which we saw is directly related to the breakdown of family structure, personal responsibility and social order in too many areas of our society."[185] Similarly, White House Press Secretary Marlin Fitzwater alleged that "many of the root problems that have resulted in inner-city difficulties were started in the 1960s and 1970s and ... they have failed ... [N]ow we are paying the price."[186]

Writers for former Congressman Ron Paul framed the riots in similar terms in the June 1992 edition of the Ron Paul Political Newsletter, billed as a special issue focusing on "racial terrorism".[187] "Order was only restored in LA", the newsletter read, "when it came time for the blacks to pick up their welfare checks three days after rioting began ... What if the checks had never arrived? No doubt, the blacks would have fully privatized the welfare state through continued looting. But they were paid off, and the violence subsided."[188] Paul later disavowed the newsletter and stated he did not exercise direct oversight on its content, but accepted “moral responsibility” for it being published under his name.[189]

Rodney King

[edit]In the aftermath of the riots, public pressure mounted for a retrial of the officers. Federal charges of civil rights violations were brought against them. As the first anniversary of the acquittal neared, the city tensely awaited the federal jury's decision.

The decision was read in a court session on Saturday, April 17, 1993, at 7 a.m. Officer Laurence Powell and Sergeant Stacey Koon were found guilty, while officers Theodore Briseno and Timothy Wind were acquitted. Mindful of criticism of sensationalist reporting after the first trial and during the riots, media outlets opted for more sober coverage.[190] Police were fully mobilized with officers on 12 hour shifts, convoy patrols, scout helicopters, street barricades, tactical command centers, and support from the Army National Guard, the active duty Army and the Marines.[191][192]

All four of the officers left or were fired from the LAPD. Briseno left the LAPD after being acquitted on both state and federal charges. Wind, who was also twice acquitted, was fired after the appointment of Willie L. Williams as Chief of Police. The Los Angeles Police Commission declined to renew Williams's contract, citing failure to fulfill his mandate to create meaningful change in the department.[193]

Susan Clemmer, an officer who gave crucial testimony for the defense during the officers' first trial, committed suicide in July 2009 in the lobby of a Los Angeles Sheriff's Station. She had ridden in the ambulance with King and testified that he was laughing and spat blood on her uniform. She had remained in law enforcement and was a Sheriff's Detective at the time of her death.[194][195]

Rodney King was awarded $3.8 million in damages from the City of Los Angeles. He invested most of this money in founding a hip-hop record label, "Straight Alta-Pazz Records". The venture was unable to garner success and soon folded. King was later arrested at least eleven times on a variety of charges, including domestic abuse and hit and run.[59][196] King and his family moved from Los Angeles to San Bernardino County's Rialto suburb in an attempt to escape the fame and notoriety and begin a new life.

King and his family later returned to Los Angeles, where they ran a family-owned construction company. Until his death on June 17, 2012, King rarely discussed the night of his beating by police or its aftermath, preferring to remain out of the spotlight. King died of an accidental drowning; authorities said that he had alcohol and drugs in his body. Renee Campbell, his most recent attorney, described King as "... simply a very nice man caught in a very unfortunate situation."[197]

Arrests

[edit]On May 3, 1992, in view of the large number of persons arrested during the riots, the California Supreme Court extended the deadline to charge defendants from 48 hours to 96 hours. That day, 6,345 people were arrested.[20] Nearly one third of the rioters arrested were released because police officers were unable to identify individuals in the sheer volume of the crowd. In one case, officers arrested around 40 people stealing from one store; while they were identifying them, a group of another 12 looters were brought in. With the groups mingled, charges could not be brought against individuals for stealing from specific stores, and the police had to release them all.[198]

In the weeks after the rioting, more than 11,000 people were arrested.[199] Many of the looters in black communities were turned in by their neighbors, who were angry about the destruction of businesses who employed locals and provided basic needs such as groceries. Many of the looters, fearful of prosecution by law enforcement and condemnation from their neighbors, ended up placing looted items curbside in other neighborhoods to get rid of them.[citation needed]

Rebuilding Los Angeles

[edit]

After three days of arson and looting, some 3,767 buildings were affected and damaged.[200][201] and property damage was estimated at more than $1 billion.[55][202][203] Donations were given to help with food and medicine. The office of State Senator Diane E. Watson provided shovels and brooms to volunteers from all over the community who helped clean. Thirteen thousand police and military personnel were on patrol, protecting intact gas stations and food stores; they reopened along with other businesses areas such as the Universal Studios tour, dance halls, and bars. Many organizations stepped forward to rebuild Los Angeles; South Central's Operation Hope and Koreatown's Saigu and KCCD (Korean Churches for Community Development), all raised millions to repair destruction and improve economic development.[204] Singer Michael Jackson "donated $1.25 million to start a health counseling service for inner-city kids".[205] President George H. W. Bush signed a declaration of disaster; it activated federal relief efforts for the victims of looting and arson, which included grants and low-cost loans to cover their property losses.[200] The Rebuild LA program promised $6 billion in private investment to create 74,000 jobs.[203][206]

The majority of the local stores were never rebuilt.[207] Store owners had difficulty getting loans; myths about the city or at least certain neighborhoods of it arose discouraging investment and preventing growth of employment.[208] Few of the rebuilding plans were implemented, and business investors and some community members rejected South L.A.[203][207][209]

Residential life

[edit]Many Los Angeles residents bought weapons for self-defense against further violence. The 10-day waiting period in California law stymied those who wanted to purchase firearms while the riot was going on.[210]

In a survey of local residents in 2010, 77 percent felt that the economic situation in Los Angeles had significantly worsened since 1992.[204] From 1992 to 2007, the black population dropped by 123,000, while the Latino population grew more than 450,000.[207] According to the Los Angeles police statistics, violent crime fell by 76 percent between 1992 and 2010, which was a period of declining crime across the country. It was accompanied by lessening tensions between racial groups.[211] In 2012, sixty percent of residents reported racial tension had improved in the past 20 years, and the majority said gang activity had also decreased.[212]

In popular culture

[edit]The 2004 video game Grand Theft Auto: San Andreas - which takes place in a parody of Los Angeles called Los Santos - features riots inspired by the LA riots that occur toward the end of the main story.[213]

American punk, rock, ska band Sublime wrote a song about the LA riots titled, "April 29, 1992 (Miami)" which is featured on their eponymous album Sublime in 1996. The lyrics describe the first day of the riots as seen in the eyes of the band members, as well as riots breaking out in the rest of the country.

See also

[edit]- 1992 Los Angeles riots in popular culture

- Rooftop Koreans

- 1981 Brixton riot

- 1980 Miami riots

- 2011 London riots

- 2015 Baltimore protests

- 2020–2023 United States racial unrest

- Attack on Reginald Denny

- The Riot Within: My Journey from Rebellion to Redemption

- Murders of Ming Qu and Ying Wu

- 1991 Crown Heights riot

- Driving while black

- Ferguson unrest

- King assassination riots

- List of ethnic riots in the United States

- List of incidents of civil unrest in the United States

- Mass racial violence in the United States

- May 1998 riots of Indonesia

- Police brutality in the United States

- Racial profiling

- Race in the United States criminal justice system

- Racism against Black Americans

- Racism in the United States

- Long, hot summer of 1967

- George Floyd protests

- Killing of Trayvon Martin

Simultaneous 1992 riots:

Other Los Angeles riots:

- Watts riots (1965)

- Zoot suit riots (1943)

- George Floyd unrest (2020)

References

[edit]- ^ Mydans, Seth (May 3, 1992). "RIOT IN LOS ANGLES: Pocket of Tension; A Target of Rioters, Koreatown is Bitter, Armed and Determined". The New York Times.

- ^ "Los Angeles Riots: Remember the 63 people who died". April 26, 2012.

- ^ Harris, Paul (1999). Black Rage Confronts the Law. NYU Press. p. 186. ISBN 9780814735923. Retrieved October 25, 2017.

- ^ Rayner, Richard (1998). The Granta Book of Reportage. Granta Books. p. 424. ISBN 9781862071933. Retrieved October 25, 2017.

- ^ Danver, Steven L., ed. (2011). "Los Angeles Uprising (1992)". Revolts, Protests, Demonstrations, and Rebellions in American History: An Encyclopedia, Volume 3. Santa Barbara, Calif.: ABC-CLIO. pp. 1095–1100. ISBN 978-1-59884-222-7.

- ^ a b Bergesen, Albert; Herman, Max (1998). "Immigration, Race, and Riot: The 1992 Los Angeles Uprising". American Sociological Review. 63 (1): 39–54. doi:10.2307/2657476. JSTOR 2657476.

- ^ "Trump invoking Insurrection Act could undo years of police reform, experts warn". NBC News. June 4, 2020. Retrieved December 27, 2021.

- ^ Miranda, Carolina A. (April 28, 2017). "Of the 63 people killed during '92 riots, 23 deaths remain unsolved – artist Jeff Beall is mapping where they fell". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Cannon, Lou; Lee, Gary (May 2, 1992). "Much Of Blame Is Laid On Chief Gates". The Washington Post. Retrieved November 22, 2018.

- ^ Mydans, Seth (October 22, 1992). "Failures of City Blamed for Riot In Los Angeles". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 23, 2018. Retrieved November 23, 2018.

- ^ a b "The Final Report: The L.A. Riots", National Geographic Channel, aired on October 4, 2006, 10 pm EDT, approximately 38 minutes into the hour (including commercial breaks).

- ^ "Violence and Racism Are Routine In Los Angeles Police, Study Says". www.nytimes.com. July 10, 1991. Retrieved April 19, 2017.

- ^ Cannon, Lou; Lee, Gary (May 2, 1992). "Much Of Blame Is Laid On Chief Gates". The Washington Post. Retrieved November 22, 2018.

- ^ Mydans, Seth (October 22, 1992). "Failures of City Blamed for Riot In Los Angeles". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 23, 2018. Retrieved November 23, 2018.

- ^ Schrader, Stuart (2019). Badges without Borders: How Global Counterinsurgency Transformed American Policing. Vol. 56. University of California Press. p. 216. doi:10.2307/j.ctvp2n2kv. ISBN 978-0-520-29561-2. JSTOR j.ctvp2n2kv. S2CID 204688900.

- ^ Zirin, Dave (April 30, 2012). "Want to Understand the 1992 LA Riots? Start with the 1984 LA Olympics". The Nation.

- ^ Cockburn, Alexander; Jeffrey St. Clair (1998). Whiteout: The CIA, Drugs, and the Press. Verso. p. 77. ISBN 978-1-85984-139-6.

- ^ Moody, Mia Nodeen (2008). Black and Mainstream Press' Framing of Racial Profiling: A Historical Perspective. University Press of America. p. 14. ISBN 978-0-7618-4036-7.

- ^ Kato, M. T. (2007). From Kung Fu to Hip Hop: globalization, revolution, and popular culture. SUNY Press. pp. 173–174. ISBN 978-0-7914-6991-0.

- ^ a b c Reinhold, Robert (May 3, 1992). "Riots in Los Angeles: The Overview; cleanup begins in los angeles; troops enforce surreal calm". The New York Times. Retrieved November 19, 2012.

- ^ Parvini, Sarah; Kim, Victoria (April 29, 2017). "25 years after racial tensions erupted, black and Korean communities reflect on L.A. riots". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved June 28, 2020.

- ^ Bradshaw, Peter (August 2, 2019). "Do the Right Thing review – Spike Lee's towering, timeless tour de force". The Guardian. Retrieved June 28, 2020.

- ^ Sastry, Anjuli; Bates, Karen Grigsby (April 26, 2017). "When LA Erupted In Anger: A Look Back At The Rodney King Riots". NPR. Retrieved December 5, 2020.

- ^ "How Koreatown Rose From The Ashes Of L.A. Riots". NPR. April 27, 2012. Retrieved May 3, 2014.

- ^ "When LA Erupted In Anger: A Look Back At The Rodney King Riots". National Public Radio. April 26, 2017.

- ^ People v. Superior Court of Los Angeles County (Du), 5 Cal. App. 4th 822, 7 Cal.Rptr.2d 177 (1992), from Google Scholar. Retrieved on September 14, 2012.

- ^ Holguin, Rick; Lee, John H. (June 18, 1991). "Boycott of Store Where Man Was Killed Is Urged : Racial tensions: The African American was slain while allegedly trying to rob the market owned by a Korean American". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved May 30, 2020.

- ^ Serrano, Richard A. (March 30, 1991). "Officers Claimed Self-Defense in Beating of King". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved May 29, 2020.

- ^ "Sergeant Says King Appeared to Be on Drugs". The New York Times. March 20, 1992. Retrieved March 4, 2011.

- ^ Swift, David (July 10, 2020). "More than black and white". Standpoint. Archived from the original on November 28, 2020. Retrieved December 29, 2020.

- ^ "Sergeant Says King Appeared to Be on Drugs". The New York Times. March 20, 1992.

- ^ Faragher, John. "Rodney King tape on national news". YouTube. Retrieved June 19, 2014.

- ^ "Prosecution Rests Case in Rodney King Beating Trial". tech.mit.edu – The Tech. Archived from the original on March 5, 2016. Retrieved May 12, 2016.

- ^ Gonzalez, Juan (June 20, 2012). "George Holliday, the man with the camera who shot Rodney King while police subdued him, got burned, too. He got a quick thanks from King, but history-making video brought him peanuts and even the camera was finally yanked away". Daily News. New York. Retrieved June 19, 2014.

- ^ Doug Linder. "The Arrest Record of Rodney King". Law.umkc.edu. Archived from the original on September 11, 2010. Retrieved August 11, 2010.

- ^ Official Negligence: How Rodney King and the Riots Changed Los Angeles and the LAPD[permanent dead link] pp. 41–42

- ^ "Los Angeles Times: Archives". Pqasb.pqarchiver.com. Archived from the original on January 11, 2012. Retrieved August 11, 2010.

- ^ "The New York Times: Search for 'rodney king'". The New York Times. Retrieved August 11, 2010.[verification needed]

- ^ "Archives: Chicago Tribune". Pqasb.pqarchiver.com. Archived from the original on January 11, 2012. Retrieved August 11, 2010.

- ^ "Uprising: Hip Hop & The LA Riots". Retrieved November 3, 2013.

- ^ "Baltimore Is Everywhere: A Partial Culling of Unrest Across America", (Condensed from the Encyclopedia of American Race Riots, ed. Walter Rucker and James Nathaniel Upton), New York magazine, May 18–31, 2015, p. 33.

- ^ Mydans, Seth (March 6, 1992). "Police Beating Trial Opens With Replay of Videotape". The New York Times. Retrieved April 20, 2010.

- ^ Abcarian, Robin (May 7, 2017). "An aggravating anniversary for Simi Valley, where a not-guilty verdict sparked the '92 L.A. riots". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved May 7, 2017.

- ^ Serrano, Richard (March 3, 1992). "Jury Picked for King Trial; No Blacks Chosen". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved March 4, 2020.

- ^ "Rodney King Juror Talks About His Black Father and Family For the First Time". laist. April 28, 2012. Archived from the original on May 4, 2012. Retrieved March 8, 2013.

- ^ a b "After the riots; A Juror Describes the Ordeal of Deliberations". The New York Times. May 6, 1992. Retrieved March 4, 2011.

- ^ "Jurist – The Rodney King Beating Trials". Jurist.law.pitt.edu. Archived from the original on August 26, 2010. Retrieved August 11, 2010.

- ^ Law.umkc.edu Archived April 17, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Online NewsHour Forum: Authors' Corner with Lou Cannon – April 7, 1998". Pbs.org. Archived from the original on August 12, 2010. Retrieved August 11, 2010.

- ^ Serrano, Richard A. (April 30, 1992). "All 4 Acquitted in King Beating : Verdict Stirs Outrage; Bradley Calls It Senseless: Trial: Ventura County jury rejects charges of excessive force in episode captured on videotape. A mistrial is declared on one count against Officer Powell". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ doug linder. "videotape". Law.umkc.edu. Archived from the original on August 23, 2010. Retrieved August 11, 2010.

- ^ The American edition of the National Geographic Channel aired the program "The Final Report: The L.A. Riots" on October 4, 2006 10 pm EDT, approximately 27 minutes into the hour (including commercial breaks).

- ^ a b c Cannon, Lou (1999). Official Negligence: How Rodney King and the Riots Changed Los Angeles and the LAPD (Reprint ed.). Basic Books. p. 284. ISBN 978-0813337258.

- ^ CNN Documentary Race + Rage: The Beating of Rodney King, aired originally on March 5, 2011; approximately 14 minutes into the hour (not including commercial breaks).

- ^ a b "Los Angeles Riots Fast Facts". CNN. September 18, 2013. Retrieved November 11, 2015.

- ^ "Deaths during the L.A. riots". Los Angeles Times. April 25, 2012.

- ^ "Deaths during the LA Riots". Los Angeles Times. April 25, 2012. Retrieved July 21, 2020.

- ^ Sullivan, Meg (July 8, 2013). "New book by UCLA historian traces role of gender in 1992 Los Angeles riots". UCLA Newsroom. Retrieved June 24, 2017.

- ^ a b Madison Gray (April 25, 2007). "The L.A. Riots: 15 Years After Rodney King". Time. Archived from the original on April 29, 2007.

- ^ Daniel B. Wood (April 29, 2002). "L.A.'s darkest days". The Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved January 18, 2010.

- ^ Pastor, M. (1995). "Economic Inequality, Latino Poverty, and the Civil Unrest in Los Angeles". Economic Development Quarterly. 9 (3): 238–258. doi:10.1177/089124249500900305. S2CID 153387638.

- ^ a b Peter Kwong, "The First Multicultural Riots", in Don Hazen (ed.), Inside the L.A. Riots: What Really Happened – and Why It Will Happen Again, Institute for Alternative Journalism, 1992, p. 89.

- ^ LA Riots EBS Message (SSTEAS Reupload). Izzy Star. February 3, 2020. Archived from the original on October 21, 2022. Retrieved December 8, 2022 – via YouTube.

- ^ a b c Rosegrant, Susan (2000). The Flawed Emergency Response to the 1992 Los Angeles Riots. OCLC 50255450.