Connecticut Colony

Connecticut Colony | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1636–1776 | |||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Status | Colony of England (1636–1707) Colony of Great Britain (1707–1776) | ||||||||||

| Capital | Hartford (1636–1776) New Haven (joint capital with Hartford, 1701–76) | ||||||||||

| Common languages | English, Mohegan-Pequot, and Quiripi | ||||||||||

| Religion | Congregationalism (official)[1] | ||||||||||

| Government | Self-governing colony | ||||||||||

| Governor | |||||||||||

• 1639-1640 | John Haynes (first) | ||||||||||

• 1769-1776 | Jonathan Trumbull (last) | ||||||||||

| Legislature | General Court | ||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||

• Established | March 3, 1636 | ||||||||||

• Fundamental Orders of Connecticut adopted | January 14, 1639 | ||||||||||

• Royal Charter granted | October 9, 1662 | ||||||||||

• Part of the Dominion of New England | 1686-89 | ||||||||||

• Independence | July 4, 1776 1776 | ||||||||||

| Currency | Connecticut pound | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Today part of | ∟ | ||||||||||

The Connecticut Colony, originally known as the Connecticut River Colony, was an English colony in New England which later became the state of Connecticut. It was organized on March 3, 1636, as a settlement for a Puritan congregation of settlers from the Massachusetts Bay Colony led by Thomas Hooker. The English would secure their control of the region in the Pequot War. Over the course of the colony's history it would absorb the neighboring New Haven and Saybrook colonies. The colony was part of the briefly-lived Dominion of New England. The colony's founding document, the Fundamental Orders of Connecticut has been called the first written constitution of a democratic government, earning Connecticut the nickname "The Constitution State".[2]

History

[edit]Prior to European settlement, the land that would become Connecticut was home to the Wappinger Confederacy along the western coast and the Niantics on the eastern coast. Further inland were the Pequot, who pushed the Niantic to the coast and would become the most important tribe in relations with colonists. Also present were the Nipmunks and Mohicans, though these two tribes largely lived in the neighboring states of Massachusetts and New York respectively.[3] The first European to visit Connecticut was Dutch explorer Adriaen Block, who sailed up the Connecticut River with his yacht Onrust.[4][5] Accordingly, as the first Europeans to explore Connecticut, the Dutch claimed the land as part of New Netherland and negotiated a land purchase of 20 acres along the river from Wopigwooit, the Grand Sachem of the Pequot in 1633. The Dutch would establish a trading post named Kivett's Point and a redoubt named Fort Good Hope, the future sites of Saybrook and Hartford respectively.[6][7][8]

English settlement

[edit]In 1631, a group of sachems from the Connecticut valley led by Wahquimacut visited Plymouth Colony and Boston, asking both colonies to send settlers to Connecticut to fight the Pequot. Massachusetts governor John Winthrop rejected the proposal but Edward Winslow, governor of Plymouth was more open, traveling to Connecticut in person in 1632.[9] Winslow, along with William Bradford would later travel to Boston to convince the leaders of Massachusetts Bay to join Plymouth in constructing a trading post on the Connecticut River before the Dutch could. Winthrop rejected the offer, calling Connecticut "not fit to meddle with" citing hostile Indians and the difficulty of moving large ships into the Connecticut River.[10][11][12]

Despite the Bay Colony's refusal to join the venture, Plymouth sent a bark led by William Holmes to establish a trading post on the Connecticut. Besides the English settlers, they took some of the original sachems of the area to prove the validity of their claim. As they passed Fort Good Hope they were threatened by the Dutch, a threat ignored by Holmes. Holmes proceeded a few miles up river and constructed a trading post on the modern site of Windsor.[13][14] Hearing of the English activities, New Netherland governor Wouter Van Twiller dispatched 70 men to dislodge the English. The Dutch would find the English well prepared to defend themselves and left, seeking to avoid bloodshed.[15] Meanwhile, John Oldham led a group of men from the Bay Colony to the river to see Connecticut for themselves. They returned with accounts of plentiful beaver, hemp, and graphite. A year later, Oldham would lead a group of settlers to found the town of Wethersfield.[13][16]

By 1635, Massachusetts' English population had grown immensely and it was clear there was not enough land for the settlers. Particularly eager to leave the crowded Bay colony were the residents of Newtown. The founder of Newtown, Thomas Dudley was frequently at odds with Winthrop, including anger at the choice of Boston as the colony's capital and refusal to support the construction of a fort in Boston.[17] Dudley sent one Thomas Hooker, Newtown's pastor to Boston to resolve the latter dispute, but the resentment of Winthrop remained.[18][19] After Dudley replaced Winthrop as governor in May 1634, the issue of Hooker's congregation's desire for removal to Connecticut was raised in the General Court. Opponents of the removal countered with a proposal that settlers instead settle Agawam and Merrimack. Both sites proved unsatisfactory, but removal was nonetheless delayed for two years.[20][21]

Despite the refusal of Thomas Hooker's request for removal, settlers continued to pour into the valley. In May 1635 the Saybrook Colony was established at the mouth of the Connecticut River.[22] Considerable amounts of emigrants from Massachusetts also settled in the recently established town of Wethersfield.[23] Plymouth's settlement of Windsor also found itself swamped by settlers from Dorchester who took over the settlement. The issue was resolved when the Dorchester settlers agreed to pay the Plymouth settlers for the land appropriated.[24] Finally in 1636 the arrival of a new group of settlers allowed Hooker's congregation to sell their homes and set off on the journey to Connecticut on the May 31.[25]

Hooker's group of around a hundred settlers and as many cattle soon arrived at the Connecticut River and established the town of Newtown near the Dutch fort. This name would not last however, as it was soon renamed Hartford after Hertford, the hometown of settler Samuel Stone.[26] In May 1638 Thomas Hooker delivered a sermon on civil government. Inspired by this sermon the settlers sought to create a constitution for the colony. The resulting document, the Fundamental Orders of Connecticut, was likely mostly drafted by Roger Ludlow, the only trained lawyer in the colonies. The document was adopted in January 1639 and formally united the settlements of Hartford, Windsor, and Wetherfield together and has been called the first written democratic constitution.[2][27][28] Under the new constitution, John Haynes was elected governor with Ludlow as deputy governor. Owing to a restriction against governors seeking office in consecutive years, Haynes would alternate the office of governor with Edward Hopkins every year until 1655.[29] Shortly after the Fundamental Orders were established, the nearby New Haven colony organized its own government.[30]

Pequot War

[edit]When Fort Good Hope was constructed, the Dutch specified in their treaty with the Pequot that the trading post was to be open to all tribes. Ignoring this, the Pequot attacked a rival tribe attempting to trade. The Dutch retaliated by kidnapping the sachem of the Pequot, Tatobem and holding him for ransom. After the Pequot paid the ransom, the Dutch gave them Tatobem's corpse. The Pequot retaliated for this by attacking an English ship, believing it to be Dutch. The ship's captain, John Stone, and his crew were killed by the Pequot.[31] A Pequot envoy was sent to Massachusetts to explain the misunderstanding. The envoy told the English about the mistaken identity of the ship. When asked to turn over the killers, the envoy claimed all but two of the killers had died of a recent smallpox epidemic and they lacked the authority to turn over the two survivors. The Pequot further claimed the killing was justified as Stone had captured two Pequots and mistreated them.[32] When John Gallup was sailing to Long Island he spotted a pinnace belonging to John Oldham, its deck covered with Indians. When Gallup attempted to board the ship to investigate, a fight ensued with Gallup victorious. The colonists blamed the Narragansett for the killing, warning Roger Williams to be careful. The Narragansett leaders Canonicus and Miantonomoh were able to reassure the colonist, claiming that the culprits not killed by Gallup were hiding among the Pequot.[33]

After this a group of ninety men led by John Endecott and his captains John Underhill and Nathaniel Turner was sent from Massachusetts to the Pequot's territory to demand the return of the murderers of both Stone and Oldham. The force first sailed to Block Island, but the Indians evaded them there and the force left with the only casualty inflicted on the villagers being the burning of the island's empty villages.[34] When the forced arrived in Pequot territory, they were told that the murder was committed by none other than Sassacus, grand sachem of the Pequot. The Pequot also claimed to be unable to distinguish the Dutch from the English. Disbelieving these claims and seeing there were no women or children among the Pequot, Endecott attacked, beginning the war.[35] The Pequot responded by besieging Saybrook and attacking Wethersfield, where they would kill nine and take two women hostage.[36] The women were daughters of William Swaine and would later be rescued by the Dutch.[37]

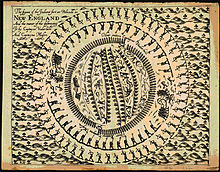

Connecticut sent a force of ninety men, led by John Mason. The force was joined by sixty Mohegans led by Uncas and came to Saybrook where a group of Massachusetts men led by Underhill joined them. On May 26, 1637, the group, encamped outside a fortified Pequot village on the Mystic River, launched a surprise attack at dawn. The English charged into the village, set it on fire, and formed a ring around the stockades to kill anyone attempting to escape. The Indian allies formed a second ring to catch anyone who managed to escape the first. Hundreds of Pequots died, many of the women and children.[38]

Their spirits broken, many of the Pequot attempted to flee west. Mason, accompanied by Israel Stoughton pursued a group of three hundred Pequots to a swamp near modern Fairfield, where they killed and captured a great number of them. Sassacus was able to escape to the Mohawks, who immediately killed him and his party, sending his scalp to Boston.[39][40] With the Pequots vanquished the Treaty of Hartford was signed between Connecticut, the Mohegans, and the Narragansett, granting the Connecticut settlers the exclusive right to the former Pequot land and dissolving the Pequot as both a political and cultural entity, with surviving Pequots made to assimilate into the other tribes.[41]

Consolidating the colony

[edit]

With the outbreak of the English Civil War, English support for the Saybrook Colony dried up. The colony's governor, George Fenwick negotiated a deal to sell the colony to Connecticut in 1644.[42] Fenwick would return to England and serve with distinction under Oliver Cromwell.[43] Inspired by the successes of colonial cooperation during the Pequot War, Connecticut, along with Massachusetts, Plymouth, and New Haven formed the New England Confederation to mutually defend the colonies against the Dutch, French, and Indians.[44][45] Before leaving for England, Fenwick, along with Hopkins, would serve as Connecticut's first commissioners to the Confederation.[46] Connecticut's membership in the Confederation also meant it sent troops to fight in King Philip's War, though Connecticut itself was minimally impacted.[47]

Like its fellow Puritan colonies, Connecticut would welcome Cromwell's victory in the civil war. The new English government, however, would soon cause issues for Connecticut. The Confederation negotiated the Treaty of Hartford defining the border between New Netherland and the English colonies, but the government in England refused to ratify it.[48] Tensions with the Dutch would be inflamed by the Navigation Act 1651, restricting foreign trade with the colonies. These tensions would culminate in the First Anglo-Dutch War.[49] The war's outbreak enabled Connecticut to seize Fort Good Hope in 1653.[50]

After the restoration of the Stuart monarchy, many in Connecticut feared their colony's Puritanism and lack of a royal charter would lead to Charles II curtailing the colony's self government. Governor John Winthrop Jr. was sent to England in 1662 where he successfully obtained a charter. The charter granted Connecticut extensive liberties, with the removal of references to royalty being the only change required in the aftermath of the American Revolution.[51] The charter also granted Connecticut extensive land claims, defining its borders as the Narragansett Bay, the Pacific Ocean, the southern border of Massachusetts and the 40th parallel north.[52] When representatives of Connecticut traveled to New Haven to show them that they were to be annexed into Connecticut, they initially met strong opposition. This opposition faded in 1664 when New Netherland was seized and renamed New York after its proprietor, the Roman Catholic Duke of York. New York's eastern boundary was defined as the Connecticut River, making New Haven within the claims of both New York and Connecticut. Unwilling to be ruled by a Catholic royalist, New Haven relented and agreed to join Connecticut.[53] The aforementioned seizure of New Netherland would also end Connecticut's claims on Long Island, as when Captain John Scott took the island he claimed it not for Connecticut but for himself.[52]

Dominion of New England

[edit]

The Duke of York would ascend to the throne as King James II and VII. As one of his first acts, he would consolidate the English colonies from West Jersey to Maine into the Dominion of New England. Sir Edmund Andros would be appointed governor of the new united colony. Andros demanded that Connecticut hand over its charter as it was no longer a separate colony. Governor Robert Treat attempted to delay handing over the charter for several months, but on October 31, 1687, Andros came to Hartford to retrieve the charter in person. Treat proceeded to give a speech well into the evening on the importance of the charter. Suddenly, a strong gust of wind came through the door, blowing out the candles. By the time the candles were relit, the charter had vanished, safely hidden away in a nearby oak tree.[54] The tree, which became known as the Charter Oak would endure as a symbol of Connecticut for generations.[55] Andros replaced Puritan officials with Anglicans and imposed heavy taxes. His salary of £1,200 exceeded the entire annual expenditure of Massachusetts' former government. When James II was overthrown in the Glorious Revolution, Andros initially attempted to suppress the news. Word did get out, and the colonists overthrew the dominion casting its government as crypto-Catholic supports of James II and themselves as loyal to the new Protestant monarchs of William III and Mary II. The dominion's short-lived experiment in centralized government ended and Connecticut, along with all the other colonies, had its charter restored.[56]

Later history

[edit]In 1701, New Haven was designated co-capital with Hartford. At the first legislative session in New Haven to create a college for the colony, with Saybrook as the site and Abraham Pierson as the first rector. Pierson would run the college from his home in Killingworth until his death in 1707, when it was finally moved to Saybrook. Saybrook would soon prove to be too remote and New Haven was able to beat out other communities for the site of the college in 1716. Two years later, when Elihu Yale made a significant donation to the college, it was renamed Yale College in his honor.[57]

The Connecticut Courant, the oldest continuously published newspaper in the United States, was founded in Hartford in 1764.[58]

Connecticut was a staunch supporter of the American Revolution, with a fifth of the state's male population serving in the war. Jonathan Trumbull was the only colonial governor to support the patriots. Nathan Hale, the first American spy, also hailed from the colony.[59]

Religion

[edit]The original colonies along the Connecticut River and in New Haven were established by separatist Puritans who were connected with the Massachusetts and Plymouth colonies. They held Calvinist religious beliefs similar to the English Puritans, but they maintained that their congregations needed to be separated from the English state church. They had immigrated to New England during the Great Migration. In the middle of the 18th century, the government restricted voting rights with a property qualification and a church membership requirement.[60] Congregationalism was the established church in the colony by the time of the American War of Independence until it was disestablished in 1818.[61]

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1640 | 1,472 | — |

| 1650 | 4,139 | +181.2% |

| 1660 | 7,980 | +92.8% |

| 1670 | 12,603 | +57.9% |

| 1680 | 17,246 | +36.8% |

| 1690 | 21,645 | +25.5% |

| 1700 | 25,970 | +20.0% |

| 1710 | 39,450 | +51.9% |

| 1720 | 58,830 | +49.1% |

| 1730 | 75,530 | +28.4% |

| 1740 | 89,580 | +18.6% |

| 1750 | 111,280 | +24.2% |

| 1760 | 142,470 | +28.0% |

| 1770 | 183,881 | +29.1% |

| 1774 | 197,842 | +7.6% |

| 1780 | 206,701 | +4.5% |

| Source: 1640–1760;[62] 1774[63] includes New Haven Colony (1638–1664) 1770–1780[64] | ||

Economic and social history

[edit]The economy began with subsistence farming in the 17th century and developed with greater diversity and an increased focus on production for distant markets, especially the British colonies in the Caribbean. The American Revolution cut off imports from Britain and stimulated a manufacturing sector that made heavy use of the entrepreneurship and mechanical skills of the people. In the second half of the 18th century, difficulties arose from the shortage of good farmland, periodic money problems, and downward price pressures in the export market. In agriculture, there was a shift from grain to animal products.[65] The colonial government attempted to promote various commodities as export items from time to time, such as hemp, potash, and lumber, in order to bolster its economy and improve its balance of trade with Great Britain.[66]

Connecticut's domestic architecture included a wide variety of house forms. They generally reflected the dominant English heritage and architectural tradition.[67]

See also

[edit]- List of colonial governors of Connecticut

- History of the Connecticut Constitution

- Connecticut Western Reserve

- History of Springfield, Massachusetts

References

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Barck & Lefler 1958, p. 398.

- ^ a b "Early History". CT.gov.

- ^ Bingham 1962, p. 6-7.

- ^ Bingham 1962, pp. 2–5.

- ^ "Adriaen Block". The Society of Colonial Wars in the State of Connecticut. General Society of Colonial Wars.

- ^ Bingham 1962, p. 10-11.

- ^ "History of Old Saybrook". Saybrook History. Old Saybrook Historical Society.

- ^ "House of Hope | A Tour of New Netherland".

- ^ Stiles 1859, p. 9.

- ^ Bingham 1962, pp. 12–13.

- ^ Winthrop 1908, p. 103.

- ^ Bradford 2008, pp. 370–372.

- ^ a b Bingham 1962, p. 14

- ^ Stiles 1859, pp. 11–12.

- ^ Carpenter & Arthur 1854, p. 32.

- ^ Taylor 1979, pp. 3–4.

- ^ Bingham 1962, p. 17.

- ^ "Preface". Records of the Church of Christ at Cambridge in New England, 1632-1830. Boston, E. Putnam. 1906. p. iii.

- ^ Bingham 1962, pp. 19–20.

- ^ Walker 1891, p. 83.

- ^ Bingham 1962, p. 20.

- ^ Engstrom, Hugh R. Jr. (1973). "Sir Arthur Hesilrige and the Saybrook Colony". Albion: A Quarterly Journal Concerned with British Studies. 5 (3): 157–168. doi:10.2307/4048260. JSTOR 4048260.

- ^ Adams, Sherman W. (1904). The history of ancient Wethersfield, Connecticut. Grafton Press. p. 21.

- ^ Bingham 1962, pp. 24–25.

- ^ Walker 1891, pp. 91–92.

- ^ "History of Early Hartford". Society of the Descendants of the Founders of Hartford.

- ^ Besso, Michael (2012). "Thomas Hooker and His May 1638 Sermon". Early American Studies. 10 (1): 194–225. doi:10.1353/eam.2012.0002. JSTOR 23546686.

- ^ "The Fundamental Orders of Connecticut". Connecticut History. CTHUmanities. 2023.

- ^ "John Haynes". Museum of Connecticut History. 1999.

- ^ Calder, Isabel M. (1930). "John Cotton and the New Haven Colony". The New England Quarterly. 3 (1): 82–94. doi:10.2307/359461. JSTOR 359461.

- ^ DeForest, John W. (1851). History of the Indians of Connecticut : from the earliest known period to 1850. Hartford, CT: W. J. Hamersley. pp. 72–73.

- ^ Cave, Alfred A. (1992). "Who Killed John Stone? A Note on the Origins of the Pequot War". The William and Mary Quarterly. 49 (3): 509–521. doi:10.2307/2947109. JSTOR 2947109.

- ^ Vaughn, Alden T. (1962). "Pequots and Puritans: The Causes of the War of 1637". The William and Mary Quarterly. 21 (2): 256–269. doi:10.2307/1920388. JSTOR 1920388.

- ^ Cave 1996, pp. 110–113.

- ^ Cave 1996, pp. 115–117.

- ^ Taylor 1979, p. 13.

- ^ Atwater, Edward E. (1902). History of the colony of New Haven to its absorption into Connecticut. p. 610.

- ^ Taylor 1979, p. 14.

- ^ Taylor 1979, pp. 14–15.

- ^ Grandjean, Katherine A. (2011). "The Long Wake of the Pequot War". Early American Studies. 9 (2): 379–411. doi:10.1353/eam.2011.0019. JSTOR 23547653.

- ^ Grant, Daragh (2015). "The Treaty of Hartford (1638): Reconsidering Jurisdiction in Southern New England". The William and Mary Quarterly. 72 (3): 461–498. doi:10.5309/willmaryquar.72.3.0461. JSTOR 10.5309/willmaryquar.72.3.0461.

- ^ Gates, Gilman C. (1935). "Saybrook at the mouth of the Connecticut; the first one hundred years". [Orange], [New Haven], [Press of the Wilson H. Lee Co.] p. 54.

- ^ Firth, Charles. . Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 18. p. 328.

- ^ "Avalon Project – the Articles of Confederation of the United Colonies of New England; May 19, 1643".

- ^ Ward, Harry M. (1961). "II. Genesis of Union". The United Colonies of New England—1643-90. New York, NY: Vantage Press. pp. 23–48.

- ^ Palfrey, John G. (1858). "Appendix". History of New England. Vol. 2. Little, Brown, and Company (New York). p. 635.

- ^ "1675 — King Philip's War". Society of Colonial Wars in the State of Connecticut. General Society of Colonial Wars.

- ^ O'Callaghan, Edmund B. History of New Netherland. New York Heritage Series. Vol. 2. New York, NY: Bartlett and Welford. pp. 151–155, 201–202.

- ^ Farnell, James E. (1964). "The Navigation Act of 1651, the First Dutch War, and the London Merchant Community". The Economic History Review. 16 (3): 439–454. doi:10.2307/2592847. JSTOR 2592847.

- ^ Jones, Frederick Robertson (1904). The History of North America, Volume IV. Philadelphia: George Barrie & Sons. p. 134.

- ^ "October 31: Connecticut's Greatest Legend Happened Today.... or Did It?". Today in Connecticut History. October 31, 2018.

- ^ a b Dunn, Richard S. (1956). "John Winthrop, Jr., Connecticut Expansionist: The Failure of His Designs on Long Island, 1663-1675". The New England Quarterly. 29 (1): 3–26. doi:10.2307/363060. JSTOR 363060.

- ^ Atwater, Edward Elias (1881). History of the Colony of New Haven to Its Absorption into Connecticut. author. pp. 467–468, 510.

- ^ "Robert Treat". Museum of Connecticut History. August 14, 2015.

- ^ "The Legend (and Souvernirs) of the Charter Oak". New England Historical Society. April 23, 2014.

- ^ Taylor, Alan (2001). American Colonies. Viking Press. pp. 277–280.

- ^ "A Brief History of Yale". Yale University.

- ^ "Older Than The Nation". Hartford Courant. December 29, 2013.

- ^ "Connecticut in the American Revolution" (PDF). Society of the Cincinnati. 2002.

- ^ Barck & Lefler 1958, pp. 258–259

- ^ Weston Janis, Mark (2021). "Connecticut 1818: From Theocracy to Toleration Connecticut 1818: From Theocracy to Toleration". University of Connecticut School of Law.

- ^ Purvis, Thomas L. (1999). Balkin, Richard (ed.). Colonial America to 1763. New York: Facts on File. pp. 128–129. ISBN 978-0816025275.

- ^ Purvis, Thomas L. (1995). Balkin, Richard (ed.). Revolutionary America 1763 to 1800. New York: Facts on File. p. 147. ISBN 978-0816025282.

- ^ "Colonial and Pre-Federal Statistics" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. p. 1168.

- ^ Daniels (1980)

- ^ Nutting (2000)

- ^ Smith (2007)

Sources

[edit]- Barck, Oscar T.; Lefler, Hugh T. (1958). Colonial America. New York: Macmillan. OCLC 1148613890 – via Internet Archive.

- Bingham, Harold J. (1962). History of Connecticut. Vol. 1. West Palm Beach, FL: Lewis Historical Publishing Company. hdl:2027/uva.x001137341. OCLC 988183351 – via HathiTrust.

- Bradford, William (2008). History of Plimoth Plantation. Gutenburg Project. OCLC 654227960, 680468168, 807361047.

- Carpenter, William Henry; Arthur, Timothy Shay, eds. (1854). The History of Connecticut from its earliest settlement to the present time. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Grambo & Co. hdl:2027/uc1.31158010568151. OCLC 642658909 – via HathiTrust.

- Cave, Alfred A. (1996). The Pequot War. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press. ISBN 978-0-585-08324-7. OCLC 43475458 – via Internet Archive.

- Daniels, Bruce C. (1980). "Economic development in colonial and revolutionary Connecticut: an overview". William and Mary Quarterly. 37 (3): 429–450. doi:10.2307/1923811. JSTOR 1923811.

- Nutting, P. Bradley (2000). "Colonial Connecticut's search for a staple: a mercantile paradox". New England Journal of History. 57 (1): 58–69.

- Smith, Ann Y. (2007). "A New Look at the Early Domestic Architecture of Connecticut". Connecticut History Review. 46 (1): 16–44. doi:10.2307/44369757. JSTOR 44369757. S2CID 254492604.

- Stiles, Henry Reed (1859). The history of ancient Windsor, Connecticut. New York, NY: Charles B. Norton. ISBN 978-0-7884-0706-2.

- Taylor, Robert J. (1979). Colonial Connecticut: A History. Milwood, NY: KTO Press.

- Walker, George L. (1891). Thomas Hooker: Preacher, Founder, Democrat. New York, NY: Dodd, Mead, and Company.

- Winthrop, John (1908). History of New England (PDF). Marblehead, MA: Marblehead Museum.

Further reading

[edit]- Andrews, Charles M. The Colonial Period of American History: The Settlements, volume 2 (1936) pp 67–194, by leading scholar

- Atwater, Edward Elias (1881). History of the Colony of New Haven to Its Absorption into Connecticut. author. to 1664

- Berkin, Carol (1996). First Generations: Women in Colonial America. New York, NY: Hill and Wang. ISBN 978-0-8090-1606-8.

- Burpee, Charles W. The story of Connecticut (4 vol 1939); detailed narrative in vol 1-2

- Bushman, Richard L. (1993). The Refinement of America: Persons, Houses, Cities. New York, NY: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-679-74414-6.

- Butler, Jon (1990). Awash in a Sea of Faith: Christianizing the American People. London: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-67405-601-5.

- Clark, George Larkin. A History of Connecticut: Its People and Institutions (1914) 608 pp; based on solid scholarship online

- Federal Writers' Project. Connecticut: A Guide to its Roads, Lore, and People (1940) famous WPA guide to history and to all the towns online

- Fraser, Bruce. Land of Steady Habits: A Brief History of Connecticut (1988), 80 pp, from state historical society

- Green, Jack P.; Pole, J. R. (1984). Colonial British America: Essays in the New History of the Early Modern Era. Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 9780801830556.

- Hollister, Gideon Hiram (1855). The History of Connecticut: From the First Settlement of the Colony to the Adoption of the Present Constitution. Durrie and Peck., vol. 1 to 1740s

- Hull, Brooks B.; Moran, Gerald F. (1999). "The churching of colonial Connecticut: a case study" (PDF). Review of Religious Research. 41 (2): 165–183. doi:10.2307/3512105. hdl:2027.42/60435. JSTOR 3512105.

- Jones, Mary Jeanne Anderson. Congregational Commonwealth: Connecticut, 1636–1662 (1968)

- Lipman, Andrew (2008). ""A meanes to knitt them togeather": the exchange of body parts in the Pequot War". William and Mary Quarterly. third series. 65 (1): 3–28. JSTOR 25096768.

- Roth, David M. and Freeman Meyer. From Revolution to Constitution: Connecticut, 1763–1818 (Series in Connecticut history) (1975) 111pp

- Sanford, Elias Benjamin (1887). A history of Connecticut. S.S. Scranton.; very old textbook; strongest on military history, and schools

- Taylor, Robert Joseph. Colonial Connecticut: A History (1979); standard scholarly history

- Trumbull, Benjamin (1818). Complete History of Connecticut, Civil and Ecclesiastical. very old history; to 1764

- Van Dusen, Albert E. Connecticut A Fully Illustrated History of the State from the Seventeenth Century to the Present (1961) 470pp the standard survey to 1960, by a leading scholar

- Van Dusen, Albert E. Puritans against the wilderness: Connecticut history to 1763 (Series in Connecticut history) 150pp (1975)

- Williams, Peter W., ed. (1999). Perspectives on American Religion and Culture. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishers. ISBN 978-1-5771-8117-0.

- Zeichner, Oscar. Connecticut's Years of Controversy, 1750–1776 (1949)

Specialized studies

[edit]- Buell, Richard Jr. Dear Liberty: Connecticut's Mobilization for the Revolutionary War (1980), major scholarly study

- Bushman, Richard L. (1970). From Puritan to Yankee: Character and the Social Order in Connecticut, 1690–1765. Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674029125.

- Collier, Christopher. Roger Sherman's Connecticut: Yankee Politics and the American Revolution (1971)

- Daniels, Bruce Colin. The Connecticut town: Growth and development, 1635–1790 (Wesleyan University Press, 1979)

- Daniels, Bruce C. "Democracy and Oligarchy in Connecticut Towns-General Assembly Office holding, 1701-1790" Social Science Quarterly (1975) 56#3 pp: 460–475.

- Fennelly, Catherine. Connecticut women in the Revolutionary era (Connecticut bicentennial series) (1975) 60pp

- Grant, Charles S. Democracy in the Connecticut Frontier Town of Kent (1970)

- Hooker, Roland Mather. The Colonial Trade of Connecticut (1936) online; 44pp

- Lambert, Edward Rodolphus (1838). History of the Colony of New Haven: Before and After the Union with Connecticut. Containing a Particular Description of the Towns which Composed that Government, Viz., New Haven, Milford, Guilford, Branford, Stamford, & Southold, L. I., with a Notice of the Towns which Have Been Set Off from "the Original Six.". Hitchcock & Stafford.

- Main, Jackson Turner. Connecticut Society in the Era of the American Revolution (pamphlet in the Connecticut bicentennial series) (1977)

- Pierson, George Wilson. History of Yale College (vol 1, 1952) scholarly history

- Selesky Harold E. War and Society in Colonial Connecticut (1990) 278 pp.

- Taylor, John M. The Witchcraft Delusion in Colonial Connecticut, 1647–1697 (1969) online

- Trumbull, James Hammond (1886). The memorial history of Hartford County, Connecticut, 1633–1884. E. L. Osgood., 700pp

Historiography

[edit]- Daniels, Bruce C. "Antiquarians and Professionals: The Historians of Colonial Connecticut", Connecticut History (1982), 23#1, pp 81–97.

- Meyer, Freeman W. "The Evolution of the Interpretation of Economic Life in Colonial Connecticut", Connecticut History (1985) 26#1 pp 33–43.

External links

[edit]- Archival collections

- Guide to the Connecticut Colony Land Deeds. Special Collections and Archives, The UC Irvine Libraries, Irvine, California.

- Other

- States and territories established in 1636

- States and territories disestablished in 1776

- 1636 establishments in Connecticut

- 1776 disestablishments in the British Empire

- Connecticut Colony

- Colonial settlements in North America

- Colonial United States (British)

- Dominion of New England

- English colonization of the Americas

- Former British colonies and protectorates in the Americas

- Former English colonies

- Thirteen Colonies

- Former Christian states